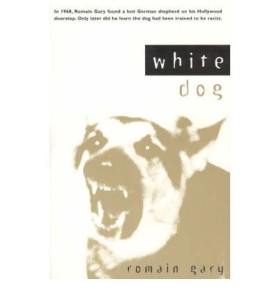

A friend loaned me this out-of-print book after we’d had a discussion about race in the United States. The story takes place in 1968 and was published two years later in France and the U.S.

A Russian émigré to France, Gary was at that time the French consul general, living in Los Angeles with his wife, actress and civil rights activist Jean Seberg, their son and several pets.

One day their sweet-natured dog brings home a new friend, a German Shepherd who seems not only gentle but extremely intelligent. All goes well until a man arrives to clean the pool—a man who happens to be black—and the dog erupts into a vicious rage.

Gary eventually discovers that this dog whom he loves and who adores him is in fact a white dog, that is, a dog who has been trained and bred to attack black people and only black people. Such dogs were used at the time by law enforcement in the South, and also as protection by whites who feared a violent black uprising—a possibility that was certainly in the air in 1968.

Though he claims to be a cynical man, Gary is seized by a rare moment of hope and resolves to train the dog not to hate anymore. Perhaps he can prove that social behavior can be unlearned, not just by this dog, but by the country itself, which has been seized by paroxysms of rage, rocked by the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy and the resulting riots.

He takes the dog to a ranch owned by a friend of his who trains animals for the movies. A black keeper there, who is expert at milking venom from snakes, makes retraining the dog his personal mission.

Gary brings a European perspective to the issues of race that were roiling the country in 1968, a time I remember only too well. Mocking non-violent activists, he circles around the idea of violence as a solution. One of his close friends is black Muslim leader calling for war against the whites—the real thing, not a metaphor. At the same time, Gary mocks the liberals—including his wife who’s become involved with funding the Black Panthers—for their posturing and ineffectual swipes at the problem.

He is not ashamed to reveal his proclivity for running away from difficult situations and spends much of the book traveling. At one point he returns to Paris in time to egg on the students rioting in the streets.

I was dismayed to discover that this supposed memoir is in fact something Gary called a fictionalized memoir. To my mind, there is no such thing. Memoirs are nonfiction, so if it is fiction then it is not a memoir.

Deliberately fictionalizing things in what is supposed to be a memoir does a disservice to all memoirs. Their power comes from the fact that they are true. Certainly it is a particular person’s truth—and we all know how different that can be from one person to another—and they have been shaped by what is included and what is left out. Still, they carry the force of personal witness.

My opinion of this book went down when I learned that it was not true. I am not alone in my dismay at the mixing of fiction and memoir. Look at the howl of betrayal over James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces.

Still, it was enlightening to revisit that explosive year, and to compare it to today’s social justice movements.

Have you read a book, seen a film, or attended a lecture that has given you a different perspective on issues around race?

Over one year since reading “small great things” by Jodi Picoult, I still contemplate some of the ideas presented. A very thought-provoking story that is fiction based on an actual event.

As for film, the Netflix original, “Mudbound” was a good watch. The choices some had to make were heartbreaking.