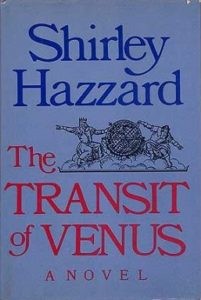

This most unusual novel, published in 1980, breaks many of the writing guidelines that have become common today.

The story ranges over wide spaces of time, leaping in and out of various characters’ lives. Similarly, the author head hops without apology, jumping between the thoughts of multiple characters in a single scene. Also, we get flash-forwards, meaning we are told in an abrupt aside of what is going to happen in the future. All of these usually pitch me out of a book, but so engaging is the prose here and so unusual the story that I was irresistibly pulled on.

The Bell sisters from Australia, recent immigrants to post-WWII England, seem to have their new lives sorted. An English-rose sort of beauty, Grace is engaged to Christian Thrale, a young bureaucrat. Caro, who is preparing to take the exam for a government post, is beautiful in her own way, a way that fits her strength and independence, Grace being more conventional.

They are staying with Christian’s parents when their plans become muddled by the introduction of two men: Ted Tice, a young astronomer from a working class background, and Paul Ivory, an up-and-coming playwright and the son of a semi-famous poet. Ted falls in love with Caro, and she with Paul, who is engaged to a wealthy neighbor.

This novel could have become a simple love triangle. However, what starts as a comedy of manners quickly becomes something more profound, as the author takes us on a fierce ride through the end of England’s empire and the attendant issues of women’s roles, colonialism, class divisions, marriage, power and the corruption it incites. Love, as well, of course—Venus is after all the ruling planet of the story—but explored in surprisingly subtle ways.

The transit referred to in the title is the rare occasion when Venus passes in front of the sun, a dark planet crossing a flaming sphere. The secrets in that dark heart are boldly drawn out in this vivid story. And its tragedies are hinted at by the early anecdote of a French astronomer who traveled to India to see the transit but missed it due to delays on the journey. He stayed there for eight years until it came around again, but the day was overcast, completely hiding the planet. The next transit wasn’t for another hundred years.

The story is rich with betrayals and subtle conflicts, as when Caro interrupts Professor Thrale’s peroration, pre-empting his reveal, and he goes on as though she hadn’t spoken. The interactions between the characters leave unusual gaps, forcing the reader to step up and fill them. Conversations are spiced with asides such as this about Mrs. Thrale:

She did not choose to have many thoughts her husband could not divine for fear she might come to despise him. Listening had been a large measure of her life: she listened closely—and, since people are accustomed to being half-heard, her attention troubled them, they felt the inadequacy of what they said.

I had a little trouble finding my footing at first, rereading the initial few pages because I thought I’d missed something. No, the author takes our intelligence for granted, giving us the opportunity to navigate her unusual and thrilling sentences in our own way.

One of the things I have come to look for and enjoy in stories is when the author treats their characters—protagonist, antagonist, and everyone else—with respect and compassion. We have that here. While it may occasionally undercut the drama, this approach finds deeper currents and insights about society in the second half of the twentieth century, shown through the lives of these two sisters, and the human condition itself.

What book have you read that, as soon as you reached the end, you turned back to begin it again?