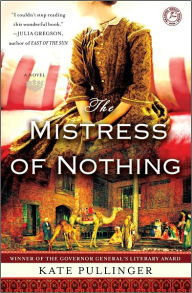

Another novel based on the lives of real people, The Mistress of Nothing is the story of Sally Naldrett, lady’s maid to Lucie, Lady Duff Gordon.

In August of 1862, thirty-year-old Sally sets sail for Egypt with her mistress, where it is hoped that the warm dry climate will ease Lady Duff Gordon’s tuberculosis. While Sally is thrilled at the prospect, having thoroughly enjoyed their previous stay in South Africa, she knows that behind Lady Duff Gordon’s brave front, her mistress is miserable.

Author of several books, translator of others, Lady Duff Gordon enjoys the scintillating company of friends such as George Meredith and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. As Sally can see, the only thing worse than leaving behind her intellectual life is the separation from her husband and children, the youngest of whom is only three. In addition to the physical suffering she endures from her advanced tuberculosis, Lady Duff Gordon resents and tries hard to hide her physical decline.

As lady’s maid, Sally tends to her mistress’s illness as well as to her clothing. When Sally declines a last-minute proposal, she declares that she is devoting her life to caring for Lady Duff Gordon.

Sally’s descriptions of Egypt are entrancing, from the crowded streets of Cairo to the time spent traveling on the Nile in their dahabieh to setting up housekeeping in Luxor. They are accompanied by a dragoman hired in Cairo, Omar Abu Halaweh. The three fall into an easy rhythm of life in Luxor, enhanced by various townspeople.

Battered by the heat, the two women shed their English clothes for loose-flowing Egyptian costumes. Both study Arabic and Islam with Omar, and the three begin to have their meals together, sitting on cushions on the floor per local custom. But differences remain. Lady Duff Gordon adopts the clothing of Egyptian men while Sally hesitates and finally choses women’s robes. Sally practices her Arabic in the marketplace while her mistress uses hers in entertaining local notables.

The English class structure is not abandoned as easily as the stiff stays that the women toss away. Sally soon finds that their free and easy their life in Luxor is an illusion. The structures of Egyptian society and politics also close in on the small household.

I raced through this novel, fascinated by the characters, entranced by the descriptions of floating on the Nile and viewing Luxor by moonlight. Most of all, I was caught up in Sally’s story, afraid of how it might turn out, shocked by some of the privileges claimed by English aristocracy that even I, with all my reading, was not aware of. If you want a good read that will also make you think about class and race and religion in new ways, this is a book for you.

In this book, the actual people involved are from the past, which makes me wonder if that is better or worse. We may be able to discover more about them now that they are gone. At the same time, they are not around to defend themselves. Pullinger has done a lot of research and I am pretty confident that the events are accurate. However, she has had to imagine the emotions and motivations of Sally, Omar and their mistress.

It is clear from her comments in the interview at the end that Pullinger has tried to follow the same advice I give in my memoir-writing classes: treat the people in your story with respect. Genuinely try to understand why they thought they were doing the right thing. Remember that each of them thinks he or she is the hero of the story.