Like Patchett’s previous novel Commonwealth, this is a story about the effects of a divorce, bonds between siblings, and coming to terms with the past.

Maeve and Danny Conroy are the siblings, whose mother Elna left when they were 10 and 3 to help the poor in India. Danny is the narrator, so all he knows is the story he was told: that she hated her life in the Dutch House, partly because it was a fabulous and gaudy mansion with a pool and landscapes grounds, and partly because her husband, real estate developer and landlord Cyril Conroy, bought it as a surprise for her in 1946, at a time when Elna thought they were dirt poor.

The house came fully furnished, with a servant named Fiona, quickly nicknamed Fluffy and joined by two sisters Jocelyn and Sandy. These three women are the ones to raise the children after their mother left, until Fluffy is dismissed for striking Danny. In many ways Maeve took over as Danny’s mother, cementing a lifelong bond between them. Then Cyril marries a young fortune-hunter named Andrea who comes with two little daughters.

Such is the setup, with the wicked stepmother taking over the house and gradually forcing Danny and Maeve out. One of the most poignant scenes for me centered on Maeve’s room, the nicest bedroom according to Danny, with a window seat overlooking the back garden. Patchett gives just enough detail for the reader to make the room her own and grieve with Maeve when she leaves it.

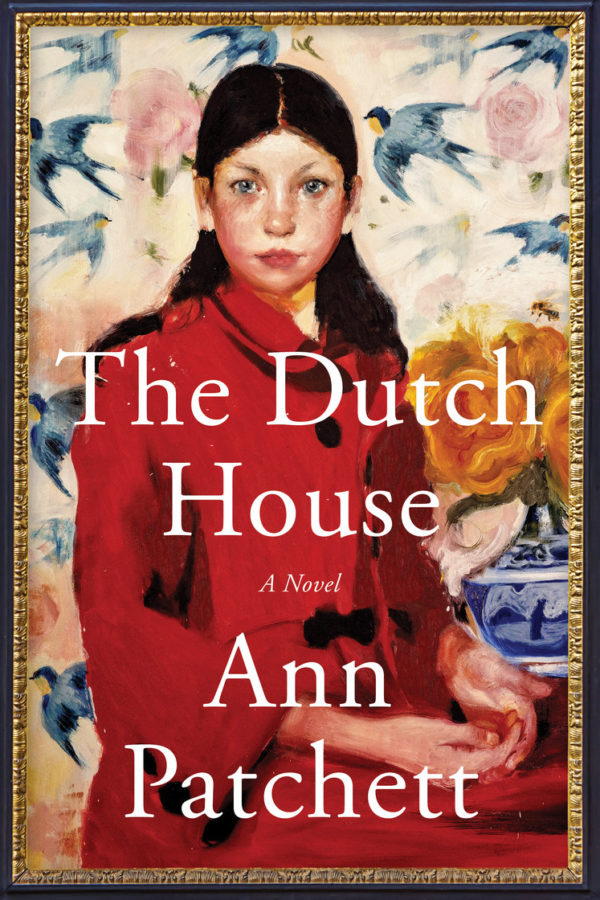

Patchett’s use of detail also works well in summoning a vision of the Dutch House: certain ornaments, some furniture on the landing, a ceiling, a ballroom on the third floor. This pastiche gives the reader a framework for envisioning the place and remembering what takes place there. The portrait of Maeve (shown on the cover of the book) gathers layers of meaning as we go through the story.

Much of the middle of the book dragged, as we learn about Danny’s life after leaving the Dutch House, his marriage and children, his work. Danny is not very emotionally aware, which sometimes made me wish Maeve were narrating the book. She’s a far more interesting character.

When the two are together, Danny visiting her in Pennsylvania, they park across the street from the Dutch House to talk about the past. In a burst of insight Danny says, “like swallows, like salmon, we were the helpless captives of our migratory patterns. We pretended that what we had lost was the house, not our mother, not our father.”

Sandy says it best, explaining why she returns to the house near the end: “The ghosts are what I come for.”

I wanted to like this book. I’m a sucker for stories about lost paradises and enchanted houses (let me tell you about mine . . . ). What I liked best about it was Tom Hanks as narrator. His distinctive voice, reassuring and trustworthy carried me over the somewhat boring stretches and the underdeveloped secondary characters.

Thinking of it as a fairy tale helped me over the unlikely plot points. As Danny notes, how does a man who doesn’t even own a char buy a mansion? Not to mention Elna leaving to work with Mother Teresa in Calcutta only a few years after the nun founded the Missionaries of Charity. And the wicked stepmother.

Patchett is an accomplished writer, so I trust that sentence by sentence the writing is good, even without Tom Hanks bringing it to life. The book has received a lot of praise and many good reviews. I’m not sure I would have finished it if I’d been reading a print book, but I’m glad I made it to the end. There’s the painting on the cover, the still somewhat mysterious and contradictory Maeve, and the lost paradise.

What story about motherless children who are also poor little rich kids have you read?

Percival James, My Name is Not Sydney Poitier. Very different kind of book, but does have that in common.