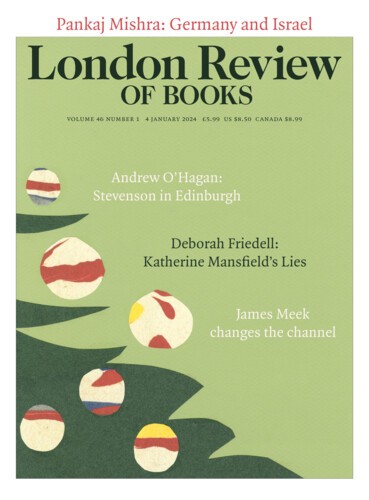

The lead article in the 4 January 2024 issue of the London Review of Books (Vol. 46 No. 1) began to sound eerily familiar. In “Say Anything, Do Anything,” James Meek reviews Pandora’s Box: The Greed, Lust and Lies that Broke Television, by Peter Biskind.

The premise of Pandora’s Box is that a series of daring, innovative shows on US cable channels, starting in the 1990s, blew away the anodyne output of the traditional TV broadcast networks.

Released from the censorship that delivered shows that were “lowest common denominator programming, comforting, predictable and morally neat,” cable channels began producing shows such as The Sopranos, Oz, The Wire, Dexter, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad. These shows were not only explicit in language and violence but featured “[a]nti-heroes like Tony Soprano, the man who garottes a fink while taking his teenage daughter on a tour of prospective colleges.”

While the movement from traditional TV shows to cable was supported by new bandwidth availability and an exponentially higher number of shows to choose from, Meek also identifies the use of algorithms to determine what viewing audiences want.

Netflix was a data-mining operation long before it got into streaming and [Reed] Hastings believed his algorithm could be used to predict the films and TV shows subscribers would like, whether they’d been made or not; if not, he’d make them.

And what did audiences want? Sports, of course, but also more nudity and lots and lots of violence. Thus, dramas like Game of Thrones became big hits.

I’m not a prude, but I am grateful that I can fast-forward through the endless nude scenes in certain dramas. Trained as a writer, I can’t help mentally wielding my red pen against gratuitous scenes that don’t move the story forward. As a woman, I can’t help suspecting these scenes are due in part to the misogynistic writers’ rooms described in Biskind’s book.

Look, I’m not here to rail against television. I have enjoyed and appreciated the craft of shows like Breaking Bad, Deadwood, and The Wire. In fact, the scene Meek calls out—”the almost loving meeting between the Baltimore drug dealers and childhood friends Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell in The Wire, where each knows the other is setting him up to be killed”—is in my opinion the single best scene in any TV drama ever.

But I don’t idolise Stringer Bell or Al Swearengen in Deadwood or Walter White in Breaking Bad. They do evil things. I appreciate that they are presented as complex characters, instead of purely evil monsters. They have their own moral codes, a line they won’t cross. Meek mentions the save-the-cat device (per Blake Snyder) of making audiences like them by having them rescue a woman or child.

What gave me chills, though, were the parts of the book about the “significant fraction” of a show’s fans that cheered the violence, demanding more, and glorifying the characters because of their evil deeds. Meek mentions the “little old ladies” who fawned over Joe Pantoliano, Ralphie in The Sopranos. Pantoliano said, “‘They were flirting with me, turned on that I was the guy who beat up this hooker. It was sick.’”

Perhaps a little disingenuously, [David] Chase said later that ‘he was troubled by how much the “less yakking, more whacking” contingent of his fan base loved his mobbed-up characters, no matter how badly they behaved. The show is “about evil”, he said. “I was surprised by how hard it was to get people to see that.”’

Evil that becomes commonplace. Evil that becomes entertainment. Evil that becomes something to cheer on. Until some people don’t even see it as evil. They applaud when a would-be dictator, already a convicted criminal, threatens to use the power of the government against his political opponents. and respond “Kill them!”

Of course, I’ve long thought about the moral damage to viewers from the bullying and cruelty of reality shows that depend on elimination, whether by firing, being voted off the island, or whatever. This part of Meek’s review hit home for me because many of these shows I’ve watched and liked. I especially appreciated the nuanced way a good man like Walter White gradually, and for reasons that seem good to him, embraces evil.

I remember the flap over films like Bonnie and Clyde and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid that glorified criminals. It seemed silly to think that watching them would make me or anyone else go out and rob a bank. I’m older now, and appreciate the more subtle ways that such things work upon our psyches. Also, that exposure a two-hours film is quite different from binge-watching five or six seasons of a TV show.

Still, I’m not advocating censorship. I’m just saying that the bloodthirsty viewers, the ones who adore their violent anti-heroes, remind me of the crowds these days baying for the blood of journalists, political opponents, immigrants—anyone they’re told to hate. I’ve been surprised by how hard it’s been to get them to see the evil in these demands. I guess I shouldn’t be. After all, they’ve been practicing this behavior night after nights in their own homes.

What TV dramas do you watch? Why?