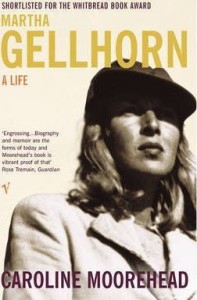

I’ve long wanted to know more about Martha Gellhorn. Moorehead’s biography brings the brilliant war correspondent to life, enhanced by the hundreds of letters Gellhorn wrote during her life, openly detailing personal and professional undertakings as well as her own thoughts and feelings.

At 29, Gellhorn went to Madrid to cover the Spanish Civil War for Collier’s Magazine. She went on to cover the twentieth century’s wars, including WWII and Vietnam, conflicts in the Middle East, Africa, and Central America, only retiring from journalism after covering the U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989, when she was 81.

She was desperate to see things for herself, visiting the front lines, talking with soldiers, looking for the little things that would make her reporting come alive. Instead of talking about strategy or interviewing generals, she preferred to write about ordinary people, just as she had in her first job as a journalist. Hired by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, she traveled around the U.S. to learn how the Depression was affecting people. That experience left her with a lifelong commitment to battling poverty by bringing it out into the open.

Gellhorn grew up in St. Louis, Missouri with a strict father, loving mother, and two brothers. Dissatisfied with this conventional upper middle class life and the narrow opportunities it offered for women, she was determined to create a life for herself. And that life was to be a foreign correspondent.

At the time, it was a highly unusual choice for a woman. Throughout her career, men held her back, officials refusing her permits and visas, publishers refusing to hire her, military officers trying to keep her away from the fighting. Even critics, enthralled by her affair and brief marriage with Ernest Hemingway, dismissed her as a pale imitation of her famous partner.

In addition to her journalism and nonfiction books about war and travel, she wrote novels and short stories, though she found writing terribly hard. Moorehead captures her conflict:

Having hitched her vision of herself so firmly to writing, and having inherited from both parents extremely high standards, Martha effectively created for herself a perilous and demanding world. If to write was her duty, her reason for being alive, then not to write was to fail. To fail as a writer was to fail at life, to be adrift in a formless and uncertain universe with nothing to hold on to.

A headstrong woman, she never backed down from the basic certainties she developed in her youth, many of them from her parents. Although she fell out with her father, who was dismayed by her flaunting of convention, shortly before his unexpected early death, she remained close to her mother, whom she called her North Star.

Passionate about her causes, Gellhorn hated dishonesty, cowardice and complacency. Although she sometimes fell out with friends, she was never happier than when hanging out with war correspondents who had become friends when they were under fire together in various hotspots. Moorehead says of her:

Something of Martha’s occasional deaf ear to the sensitivities of other people was connected, at least partly, to her strong feelings about social life . . . the world was divided between real friends—to whom she was, for the most part, very loyal and devoted—and everyone else, who mattered not at all.

Late in life she became the center of a group she called “the chaps”, men and women forty or fifty years younger that she. Writers and reporters who admired her work, which had recently become popular, they flocked to her flat in Cadogan Square. I’m glad that she was not isolated during her last years when her physical woes were mounting.

The biography is subtitled A Twentieth-Century Life. Indeed, although she was always out ahead of others, few things could be more emblematic of that turbulent century than the life of this remarkable woman who challenged customary women’s roles, stuck to her own moral code, and worked relentlessly at her chosen métier.

Have you read any of Martha Gellhorn’s work?