In 1937 Ida Mae Gladney left Mississippi for Chicago. In 1945 George Starling left Florida for New York City. In 1953 Robert Pershing Foster left Louisiana for Los Angeles.

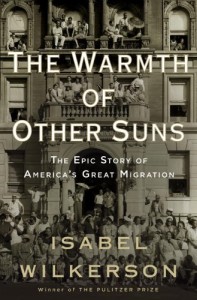

They were part of the Great Migration. From 1915 to 1970 almost six million Black citizens left the south for northern and western cities looking for better lives. For the first time Wilkerson’s monumental book gives us a history of this remarkable movement.

The book is long but eminently readable, due to Wilkerson’s approach. By closely following stories of three individuals, she captures the reader’s attention and sympathy and keeps us turning pages. There are historical sections complete with supporting statistics, but these are kept to a minimum and related to the stories we’re following. The author brings all the tools of fiction to keep us interested in this meticulously researched history.

World War I is usually considered to precipitating cause of the Great Migration. Black soldiers serving in the military and in Europe discovered that it was possible to escape Jim Crow. At the same time, factories and businesses in the north and west were desperate for workers since the flow of immigrants had basically halted and the military claimed many of the remaining men.

The scope of the Great Migration was not recognised for a long time. The effects were felt locally, in cities such as Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit, New York, but it wasn’t until southern businesses found they could no longer hire enough Black workers—whose wages had been kept artificially low by Jim Crow laws and local corruption—that the outcry began.

The last part of the book, almost one hundred pages, includes Wilkerson’s notes on her methodology, acknowledgments, endnotes and index, attesting to the solid underpinning of research. She says:

This book is essentially three projects in one. The first was a collection of oral histories from around the country. The second was the distillation of those oral histories into a narrative of three protagonists . . . The third was an examination of newspaper accounts and scholarly and literary works of the era and more recent analysis of the Migration to recount the motivations, circumstances, and perceptions of the Migration as it was in progress and to put the subjects’ actions into historical context.

It is that historical context that is the takeaway I most value from this book. Much of the information here was not new to me. Yet what stands out is how I now have a framework for all the pieces that I was already familiar with. I felt them slotting into place as I read.

One area I wish Wilkerson had covered in more depth, though obviously there wasn’t room for it, is the Black communities that flourished during segregation and then dissipated, partly through “urban renewal” demolitions and partly through integration. Wilkerson mentions it briefly in a few places, such as speaking of Harlem’s rise and fall. Robert Foster’s story, too, shows it in microcosm: as he aged, he left his prosperous private practice, where he was popular among his mostly Black patients, to join the staff of a Veterans’ Hospital. He missed being in charge and disliked having to answer to higher-ups who he believed discriminated against him, eventually forcing him out.

I will remember Robert’s story as well as those of Ida Mae and George for a long time. They brought to life the indignities of the Jim Crow South they fled and the different kinds of injustice and prejudice they found in their sanctuary cities, far worse than the discrimination that immigrants from other countries faced. Through these individuals, I have a better understanding of the people around me.

What nonfiction have you been reading?