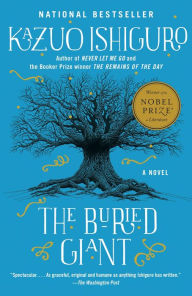

In post-Authurian Britain, an elderly couple set off to visit their son. Axl and Beatrice can’t remember when they last saw him or why they haven’t seen him in so long, although they do believe they can find the way to his village. Like everyone else around them, a mixture of Britons and Saxons, the devoted couple have been afflicted by what they call the Mist, which erases memory. On their journey they encounter many others, some of whom travel on with them.

I read this novel a few years ago, but didn’t write about it then. I didn’t quite have a handle on what I wanted to say about it. Ishiguro has long been one of my favorite authors, and I’ve been steeped in Authurian tales since childhood, so I expected to love this book.

Instead, I found it confusing and somewhat tedious. My interest picked up as I went along, though, and the end left me deeply fascinated by the ideas and experiments woven through the story. A recent book club discussion helped my crystallise further what so intrigued me.

The challenge Ishiguro faced was how to present fully developed characters when they have no memory of their past. Equally, how do you create a narrative structure when supposedly no one remembers anything from one moment to the next?

Most of the people in the book club, like me, found the book confusing and boring. Some didn’t finish it; others skimmed or skipped to the ending. One complaint was that the characters seemed two-dimensional and therefore impossible to relate to. Another was that there was a lot of repetition, especially in dialogue.

These concerns indicate that the author did not meet the challenges described above, essentially the challenge to create an engaging story. Perhaps that was not important to him; perhaps creating a vehicle for the ideas took precedence.

And the ideas are fascinating. We ended up having a long and lively discussion about them. To say more I’ll have to give away the ending, so skip this section if you don’t want the end spoiled.

***SPOILER ALERT***

At the end we discover that the mist is created by the breath of the dragon Querig, thanks to a spell by Merlin. King Arthur himself tasked Merlin to do so, to erase memory so that the Britons and Saxons could live together in peace despite the terrible battles and massacres during their long war. Only by forgetting these traumas, Arthur believed, could the cycle of revenge be broken. Killing Querig would restore people’s memory but restart resentment and hostility; they would once again be caught up in war after war.

It was this idea that so engaged us. We discussed the relevance to today’s wars, the back and forth of wars in the Balkans and the Middle East. We shared our small knowledge of the efficacy of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. One person had actually lived there for four months, so had some first-hand experience. My takeaway was that the commission succeeded in averting a civil war, but was by no means a perfect solution for living side by side with your former enemy.

How can you do that? I’ve wondered often about Rwanda, Sarajevo, and so many other homes of recent trauma. I’ve thought about the effects of horrors from before I was born, such as the Holocaust, slavery, the decimation of indigenous peoples. I’ve thought about ongoing injustices, such as the treatment of Native Americans, the new Jim Crow treatment of blacks in the U.S., the unjust wars started by the U.S., the flood of refugees, the war on poor people in the U.S. How do you live together, how do you find a way forward when you hold these long memories of injustice and suffering?

We know too much now about the longterm effects of trauma to believe there can ever be sufficient reparations to compensate for the damage inflicted, though that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

If I ever thought impatiently that people should just forgive and forget, I learned how impossible that was for me a few years ago. Meeting a man named Campbell, I mentioned that I come from a long line of MacDonalds. He understood the reference to the 1692 Massacre of Glencoe when a troop of Campbells, claiming hospitality from the Glencoe MacDonalds, rose up in the night, killing men, burning homes, and forcing women and children into the winter night where they died of exposure.

Provoked by this modern-day Campbell’s derogatory criticism of my ancestors, I found myself surprisingly roused. The two of us spent quite a while discussing this long-ago event, not so much with hostility as with a rueful recognition that it was ridiculous for us to care so much.

Recounting this episode at the book club, I said that forgetting may not be an option and that perhaps these memories of trauma serve a purpose. Challenged to explain what purpose being suspicious of Campbells might serve today, I could only respond that I thought humans’ ability to remember suffering must be a trait preserved from our earliest history, just as an animal’s ability to remember that a plant made them sick or killed one of their group saved them.

Later, though, I thought of an article I read recently about Christy Brzonkala who was raped by two football players at Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1994. Her case was taken to the Supreme Court as a test of the Violence Against Women Act where the majority ruling went against her. Her senior quote in her high school yearbook was “I will trust you until you do something to make me not trust you.”

She said she’d never learned about rape in high school. It reminded me of a remark a friend of mine, herself a product of an all-girls Catholic school, made that so many of the young women raped or murdered by boyfriends were from all-girls Catholic schools and never taught to be wary.

I thought: yes. Glencoe taught me to be wary. Glencoe taught me not to trust blindly. So, yes, that ancestral memory did serve a purpose for me.

I don’t go around carrying a sword to swing at any Campbell I meet. But I also don’t expect there are any simple solutions to the problem of living peacefully with former enemies. Expecting people to forgive and forget is not reasonable. As one person in the book club said, I do not forget; I do not forgive; but I can set it to one side. At the moment that is the best way forward that I can see.

***END OF SPOILER***

Despite our struggles with the story, we all found much to consider in Ishiguro’s examination of memory and whether forgetfulness is a blessing or a curse.

Have you read a novel about memory or forgetting? What did you think of it?