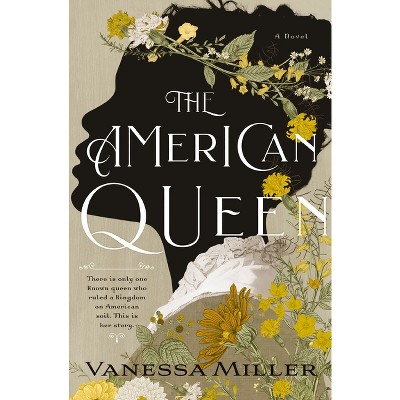

I’m always thrilled to stumble across an inspiring story based on real events, a story that’s been lost to history. In 1865, the Civil War is over, but freedom has only worsened the lives of former slaves. On the Montgomery Plantation, twenty-four-year-old Louella Bobo carries the trauma of her years as a slave: her mother being sold away, her father lynched, and beatings that have scarred her back and soul.

She hates, with all her being, and cannot find room in her heart for love, even for William, the older preacher who loves her. Still, she knows he is a good man and agrees to marry him. She knows what she wants: to make real her vision of a Happy Land where people can live freely and be treated with respect. She envisions a cooperative community, where everything is shared so that all can prosper.

When events make it impossible to stay on the plantation, Louella and William lead a group of former slaves to find a place to settle and build their community. They travel for months, encountering dangers and surprising succor in the post-Civil War South, eventually settling in the Carolinas. Louella and William are appointed Queen and King of Happy Land. It thrives, growing to 500 families, but internal friction develops and threatens all they’ve built.

Miller’s fictionalised version of this true story captures the drama of Louella’s terrible journey from hate to love. The injustice and outright abuse can be hard to read about, but will come as no surprise to anyone familiar with slavery and Reconstruction. Another aspect that can be off-putting but not unexpected for someone of the time is Louella’s devout Christianity. While no doubt historically accurate, Louella constantly excusing injustice by saying that God has His ways or hoping God would hear her need seemed to take all the air out of the story.

Luckily she often speaks her mind and finds creative ways to accomplish her goals. Such parts kept the story moving. By having Louella take the lead and speak her mind, Miller shows us a complex character. Each of the characters—and there are a lot—is fully depicted as an individual.

Given the egalitarian nature of Happy Land, I was uncomfortable with the titles of king and queen, especially since they were used as day-to-day nomenclature, i.e., referring to King William or the King and Louella likewise. Of course, this is one of the dangers of using real events for a novel. The author shouldn’t go against the actual historical record.

Having just read Erasure, a novel of how the public and the publishing industry only want and will only accept one view of The Black Experience, I appreciated this portrait of a harmonious and loving marriage as well as that of a thriving community.

The part I enjoyed most was the building of the Happy Land: how Louella managed to negotiate what they needed, the ways they found to make the money they needed, and the success of their communal sharing of all resources.

The book’s language is fairly simple; in fact, I wondered if it wasn’t a Middle Grade or Young Adult novel, though the traumatic violence rules out Middle Grade. However, it’s an easy read and an immensely valuable addition to our understanding of the time and also of what one woman can accomplish. She had a dream, and she made it come true.

What novel have you read that was based on real events?