I host a monthly poetry discussion group where we read and talk about the work of a single poet. These sessions give me, and others, a chance to explore the work of a variety of poets whom I might not otherwise have read, with the additional insight gained from everyone’s comments. As a poet myself, I have learned a lot about what different people look for in a poem, what they notice or find appealing, how they interpret certain lines. Lingering on a single poem for a time also encourages me to stay with a poem when I am reading alone and make the effort to draw back the layers, instead of reading quickly and moving on.

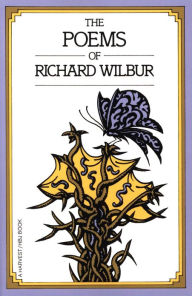

This month we read poems by Richard Wilbur. I’d heard of him: a famous twentieth century poet, he was the second poet laureate of the United States and won the Pulitzer Prize twice, the National Book Award, and many other awards and honors. However, I’d never read his work.

Known for using traditional patterns of rhyme and meter and for optimistic themes, his work fell out of favor in the 1960s and 1970s when confessional poetry and free verse became more popular. Eventually, though, the pendulum swung back again, combined with his own tendency toward more personal poems as he grew older. That was when he won his second Pulitzer and was nominated as poet laureate.

A good example of traditional form is Black Birch in Winter, with four quatrains and an AABB rhyme scheme in each. Some people were distracted by the rhymes, but we all liked the careful description of the rough bark and the way he compared it to “mosaic columns in a church” and “the trenched features of an aged man.” Trenched! We found many examples of fresh and surprising uses of familiar words as we went through the poems.

The final stanza lifted the poem into the realm of the extraordinary, where he reminds us that despite their “shriveled skin,” these trees are still “doomed to annual rebirth.”

And this is all their wisdom and their art-

To grow, stretch, crack, and not yet come apart.

As I age myself, I know I will return to these lines.

Another poem that surprised me was The Death of a Toad. Caught by a power mower, the toad manages to get to the garden and hid under the cinera leaves. While on one level the scene is about the conflict of humans with nature, on another it makes me consider our own vulnerability; a catastrophe can come out of nowhere and disrupt our destiny and all our plans. Even more, the author’s close observation of the toad and its decline reminds me to pay attention, always, no matter how trivial the subject.

We were all stunned into silence by Cottage Street, 1953, which describes a meeting over tea between Sylvia Plath and the author, hosted by Edna Ward. Ward was Wilbur’s mother-in-law who was friends with Plath’s mother, who is also present at the tea party. Did it really happen or only imagined? Doesn’t matter. What comes across so powerfully is his own humility and shame that having been invited to help her, save her, he finds himself impotent. And the two women, Edna and Sylvia, and the choices they made.

Wilbur’s most anthologised poem, Love Calls Us to the Things of This World, begins during hypnagogia, that is, the moment between sleeping and waking, before consciousness and rational thought fully take over. With images of angels and laundry and nuns, the author explores the interface between body and soul and ends with “keeping their difficult balance.”

I’m grateful for the opportunity to dig into this author’s work, and for the assistance of my fellow poetry lovers. There are so many poets and so much poetry, yet we can explore them one poet at a time, one poem at a time.

What poet have you heard of but not yet read?