This post is a continuation from last week, looking at the work of poets associated with the Harlem Renaissance, in particular those whose work I didn’t know well. There’s a great introduction to the Harlem Renaissance poets and a selection of their work at the Poetry Foundation website.

As you may know, the Harlem Renaissance is the name given to the emergence of a group of Black writers, artists, playwrights and musicians in the early 20th century when the Great Migration brought large numbers of Blacks, especially from the south, to work in northern cities. Clustered in Harlem, artists of all kinds came together, influencing and encouraging each other

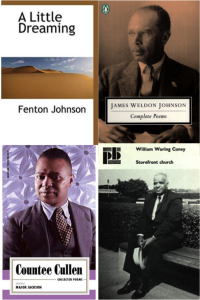

Fenton Johnson began writing and publishing before the start of the Harlem Renaissance, and spent most of his life in Chicago, where he grew up in a well-off family. Still, he is claimed by Harlem Renaissance poets as a forerunner. In addition to poetry, he wrote short stories, plays and essays. He worked as a college professor and journalist, as well as editor for several small magazines. Many of his poems take the form of spirituals, such as “How Long O Lord”:

How long, O Lord, nobody knows!

My honey’s resting near the brook.

How long, O Lord, nobody knows!

How long, O Lord, nobody knows!

I pray she’ll rise on Judgment Day.

How long, O Lord, nobody knows!

Other poems capture what it’s like to be a Black man in this society, such as “Tired” which starts “I am tired of work; I am tired of building up somebody else’s civilization” and builds to “It is better to die than it is to grow up and find out that you are colored.”

James Weldon Johnson (no relation) combined social activism with his writing activities. Head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) during the 1920s, he also found time to author studies of Black poetry, music, and theater. He’s known for his realism in his novels and for capturing the rhythms of Black life—schooled and unschooled, preachers and orators. For example, in A Poet to His Baby Son” he sees the beginnings of a poetic imagination, but cautions the child not to be a poet:

For poets no longer are makers of songs,

Chanters of the gold and purple harvest,

Sayers of the glories of earth and sky,

Of the sweet pain of love

And the keen joy of living;

No longer dreamers of the essential dreams,

And interpreters of the eternal truth,

Through the eternal beauty.

Poets these days are unfortunate fellows.

Baffled in trying to say old things in a new way

Or new things in an old language,

. . .My son, this is no time nor place for a poet;

Grow up and join the big, busy crowd

That scrambles for what it thinks it wants

Out of this old world which is—as it is—

And, probably, always will be.

Countee Cullen went in a different direction, calling for Black poets to work within a traditional framework, naming Keats and Houseman as his poetic models. Yet he wanted to reclaim African arts (a movement called Négritude) and was politically active, becoming president of the Harlem NAACP chapter. He was married to Nina Yolande DuBois, daughter of W.E.B. DuBois. No surprisingly, anger at racism was one of his main themes, as in “Yet Do I Marvel”:

I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind

And did He stoop to quibble could tell why

The little buried mole continues blind,

Why flesh that mirrors Him must some day die,

Make plain the reason tortured Tantalus

Is baited by the fickle fruit, declare

If merely brute caprice dooms Sisyphus

To struggle up a never-ending stair.

Inscrutable His ways are, and immune

To catechism by a mind too strewn

With petty cares to slightly understand

What awful brain compels His awful hand.

Yet do I marvel at this curious thing:

To make a poet black, and bid him sing.

William Waring Cuney’s musical background, attending the New England Conservatory of Music, emerges in his poetry. Infused with the rhythms of jazz and blues, his poems bounce and swing. Here’s the beginning of his tribute “Charles Parker, 1925-1955”:

Listen,

This here

Is what

Charlie

Did

To the Blues.

Listen,

That there

Is what

Charlie

Did

To the Blues.

This here,

bid-dle-dee-dee

bid-dle-dee-dee . . .

It’s interesting to see the different approaches to working within or combining various traditions. I’ll certainly be looking to read more of their poetry.

If you write poetry, what traditions influence your work? If you read poetry, what traditions are you drawn to?