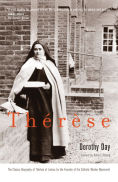

The last couple of weeks I’ve been writing about books that inspired Dorothy Day, who devoted her life to working for peace and social justice. Always her focus was on ordinary people: working people held back by low wages and bad working conditions and those most vulnerable in our society such as people living in poverty. With Peter Maurin she founded the Catholic Worker Movement with the intention of actually living according to the precepts that the Catholic church and indeed all Christian sects preach.

While I am not a Catholic myself, I turned to this short biography because Day was deeply influenced by St. Thérèse of Lisieux, also known as the Little Flower. Unlike the other Teresa, St. Teresa of Avila who was an activist and reformer as well as a mystic, Thérèse came from a humble background and lived what would seem to be an unremarkable life until her death from tuberculosis at 24.

Upon entering an enclosed Carmelite convent at the young age of 15, she spent her time in prayer and performing the hard work necessary to the community of 20 nuns, such as the back-breaking work of washing clothes by hand outdoors in winter. Near the end of her life, she was asked by the prioress to write an account of her life, an autobiography that has comforted and inspired many people

What sets her apart from other saints is her simple approach to spirituality. What she called her “little way” consists of practicing the presence of God and offering each moment to Him by making it an act of love. If another nun teased her by splashing her with dirty water, she responded with affection instead of anger. If she was assigned some hard task, she performed it without complaint, even when she was in great pain from her illness. Day says that Thérèse described these “irritations encountered in her life with twenty others under obedience . . . to show of what little things the practice of virtue is made up.”

Not all of us are broken on a wheel or shot full of arrows. The stories of most saints are dramatic and heroic. Thérèse’s everyday offering, though, is something we can all do. We can all strive to be a little bit better in everything we do.

In his Introduction, Robert Ellsberg says:

From Thérèse, Day learned that each sacrifice endured in love, each work of mercy might increase the balance of love in the world. She extended this principle to the social sphere. Each protest or witness for peace—though apparently foolish and ineffective, no more than a pebble in a pond—might send forth ripples that could transform the world . . .

Thérèse’s little way, in fact, offers an essential key to interpreting the message of Day. In a time when so many feel overwhelmed by the vast powers of this world, she bore witness to another power, one disguised in what is apparently small and weak. Certainly, life at the Catholic Worker offered daily, hourly, opportunities for self-mortification—the little decisions to sacrifice one’s time, privacy, comforts, and cravings for the sake of others. It was the practice of these small, daily choices . . . that equipped Day for the extraordinary and heroic actions she performed on a wider stage.

These days I often feel “overwhelmed by the vast powers of this world” and take comfort in the idea of small actions: a call, a postcard, a rally. I struggle to find the right balance between resisting being bullied and responding with love. This account of Thérèse’s life helps me look at these issues a different way. Complete and unquestioning obedience like hers is not right for me, but I could be more compassionate.

In a novel by Elizabeth Goudge, I read of an elderly woman in rural England during the Blitz. Unable to help those being bombed in London in any practical way due to poor health and fortune, she did the only thing she could: she prayed. My practical nature resists the idea that prayer and good intentions actually help others, but they can’t hurt, and I certainly know that some small action can have huge consequences later. We don’t know how another person may be influenced by what to us is a casual aside.

It is Thérèse’s parents whom I’ll remember from this book. Both wanted the religious life but were rejected by the holy communities they sought to enter. Day says of Thérèse’s father that “he made up his mind to live a holy life in the world.” This, to me, is the essential problem: how to live according to your ideals in this flawed world where temptations abound and compromises are the norm.

For Louis and Zélie Martin, their way was to work hard—he as a watch and clockmaker; she as a maker of fine Alençon lace—and raise their five daughters according to their beliefs. Day says of Louis “It was through marriage and the bringing up of a family that he was to play his great and saintly role in the world.” The same is true of Zélie. To the joy of both parents, all of their daughters became nuns. All are remembered for their goodness.

We can each of us play a “great and saintly role in the world” even when our lives are quite ordinary. Whatever we call our practice—compassion, mindfulness, or the presence of God—we can pursue it as our gift to the world.

What book has inspired you?