Driving around the neighborhood with my mother and sister, they would sometimes point out a house and talk about who lived there now, who used to live there, where the children ended up, and other remembered stories. We had to drive slowly since they knew and had known so many people. Besides being fun for them, the conversation helped our aging mother exercise her memory.

When I sold my house, the new buyers wanted to know about its history and everyone who had lived there before me. The latter was easy, since I had bought it from the original owners.

I often find myself thinking about, not just a house, but a piece of land and what secret history it holds. We are, after all, only borrowing this spot for now. We, too, will pass on and may or may not be remembered or sensed by those who next walk here.

In this poetry collection, subtitled Excavations and Explanations, Coultas explores that concept further in the first of its two parts. Titled The Abolition Journals (or, Tracing the Earthworks of My County), this section is about the liminal space between past and present: finding flints and arrowheads, tracing what it means to grow up in Lincoln’s land. She says, “I knew someone, an ironworker, who could point out burial and village sites in the river bottoms.”

The author also looks at the meagre boundary separating the two states her life straddles.

Looking from the free state

there is a river then a slave state

Turn around and there is a slave state,

a river

then a free state

In the second part, A Lonely Cemetery, she searches out the ghosts of these and other places. The title poem notes that it is After a line by Pablo Neruda. To Neruda’s line “There are lonely cemeteries” she adds “and there are cemeteries that wish to be alone so they send out ghosts.” In some poems she speaks for those ghosts while in others she recounts various supernatural experiences, her own and those of others: a halo around photos of a man who later survives the attack on the World Trade Center, an old woman who “was a daylight person, which is a living person who has become lost or passed into a portal,” UFOs, and an alien abduction.

I’m not quite sure what to make of this second part. Many—if not all—of us have had strange experiences. Driving in LA one day, my sister suddenly saw a person appear, touching the hood of her car before seeming to be mown down. There was no one there, but a block later, as she shakily and slowly continued to drive, a man stepped out in front of her and she was able to stop in time. I myself have twice stumbled upon places I had only seen before in dreams.

Yet I cannot say I believe in these paranormal happenings. I respect them and note them and set them aside.

The first part was more interesting to me, with its poems about the author’s native Indiana, wrestling with the history of slavery. Coultas makes interesting use of white space here, especially effective given the erasure of slaves’ names and history. The poems also wrestle with history itself, what is remembered, what buried thing is found, what no longer exists.

Some of the poems about Kentucky across the river, where a branch of her family lives, seemed odd to me, particularly the one recounting jokes making fun of Kentuckians. She says:

What did I learn about my kinfolk?

Petroglyphs mostly

divided as the bluegrass

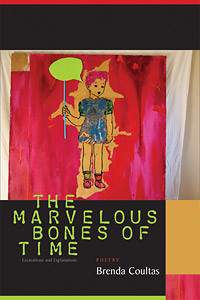

I came across this book when I was giving a reading at a bookstore in Annapolis with my friend Shirley. Attracted by the title, I pulled it out of the stack and was entranced by its cover, which features a child who looks like one of Henry Darger’s Vivian Girls. I bought it without even looking inside. Yes, I’m a reader who is seduced by titles and covers. Sometimes it’s good to be surprised.

Have you ever selected a book based on its title alone? What is the most intriguing title you’ve come across?