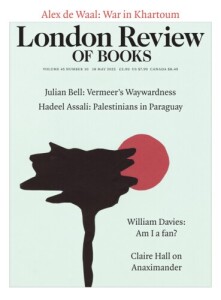

Instead of a book, this week I want to talk about an essay-length book review that has helped me understand some of the cultural trends that have mystified me. William Davies’s review of A Fan’s Life: The Agony of Victory and the Thrill of Defeat, by Paul Campos, was published in the 18 May 2023 issue of the London Review of Books.

Using football, American for the author and British for the reviewer, both dig into what it means to be a fan. While referees and judges in and out of the sports world are expected to be fair and objective, not favoring one side over another, Davies says fans “make no pretence of balance or reason. They are drunk on irrationality and obstinacy, hurling themselves after the fortunes of their chosen team, band, TV show or celebrity.”

Where it gets interesting for me is this quote from Campos: “While sports allegiances can be seen as a sublimated form of politics, political allegiances can also be understood as a form of sublimated fandom.” Some politicians have supporters who weigh a candidate’s positions on issues, proposed solutions, and their character in order to choose the person most appropriate to represent them, while other politicians have fans who don’t care how illogical or offensive the politician’s statements are.

Davies also discusses how the internet has emphasised fandom:

Once there is sufficient space for every opinion and claim to be published, what need is there for anyone to be looking down on them from a position of assumed disinterest? Fandom can become the norm instead. The internet is less a ‘marketplace of ideas’ (as conservatives and libertarians would have it) and more a ‘marketplace of passions’.

This has significant knock-on effects for the rest of the media, especially the liberal media that once sought to distinguish themselves in terms of their commitment to facts, neutrality and critical distance – values which, in a public sphere awash with fandom, can appear both technically unnecessary and culturally haughty.

As quoted in the review, Campos offers the surprising insight that “‘Sports are a form of entertainment, but deep engagement, which makes the entire sports branch of the entertainment industrial complex viable, is not about entertainment at all: it is about suffering.’” True fans stick by their team no matter how rarely they win; the nostalgia for its few successes is “integral to fan identity.”

Davies discusses “the growing difficulty Americans – especially American men – have in distinguishing ‘life’ from ‘sport’.” The concentration on men and masculinity in both the review and the book is interesting. Certainly, sports are an arena where even the most repressed men feel free to express emotion, but I think there’s plenty here that is applicable to women as well.

The review goes deeper into the connection between sports, politics and fandom, and how in politics and sports, the participation of the middle class in this kind of obsessive fandom can be traced back to a shift from snobby dismissal of the working class to wanting to join it and the subsequent flood of money into sports. Davies calls it an

embourgeoisement of the game. While middle-class men began dressing like working-class football fans, top-tier football was flooded with Rupert Murdoch’s money and the glamorous Italian players it was used to recruit – this was the beginning of the long investment wave that led to today’s multi-billion-pound industry. ‘To have been sports fans over the past few decades,’ Campos writes, ‘is to have witnessed how our passions have been identified, catalogued and then exploited by the relentless engines of hypercapitalism, in its insatiable pursuit of ever-greater profits.’

Lots here to consider in the mix of sports, politics, journalism, and capitalism.

What are you a fan of?