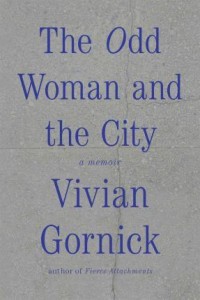

In this 2015 memoir, Gornick gives us a flâneur’s tour of New York City and of her own quirky take on life. She calls it a memoir, but to my mind it falls somewhere in the grey area between memoir and personal essay.

Author of memoirs such as Fierce Attachments and one of the best texts on writing memoir, The Situation and the Story, Gornick warns us up front that she has not only changed names but reordered certain events and used some composite characters and scenes. I have no problem with pseudonyms, but shy away from reordering and composites. To me, these take away from the truthfulness of memoir, which after all is supposed to be nonfiction. Once I start thinking of characters, scenes and timelines as not real, then the power of nonfiction seeps away like air from a balloon.

That said, I assume her thoughts and reactions are real, so I enjoyed the opportunity to spend time in her company as she walks the city streets, usually accompanied by her gay male friend Leonard (real? not real?). She says:

What we are, in fact, is a pair of solitary travelers slogging through the country of our lives, meeting up from time to time at the outer limit to give each other border reports.

Having spent a large part of my life in cities, despite or perhaps in addition to enjoying more rural settings, I appreciate her immediately setting aside the image of New York as the grand opportunity for a young male genius to prove himself. Instead she says, “Mine is the city of the melancholy Brits—Dickens, Gissing, Johnson, especially Johnson.”

She speaks of Samuel Johnson’s distrust of village life with its closed and insular society. “The meaning of the city was that it made the loneliness bearable.” Gornick calls herself an odd woman, one who finds herself on the margin of society. For her the city does more than heal loneliness; it gives her a chance to dream, to buy time to find her own way: eschewing acquisitions, turning away from the honey trap of romantic love. “I prize my hardened heart,” she says.

Her openness provides receptors where I can attach my own thoughts and experiences. When she speaks of Freud’s discovery that we are, throughout our lives, divided against ourselves and resistant to being cured, I’m reminded of the Jacqueline Rose essay I read a few weeks ago. When she mentions William James’s pronouncement that our inner lives are always in transition and that “our experience ‘lives in the transitions,’” I think of my classes where I encourage writers to explore the multiple emotions one character may experience moment to moment.

I enjoyed her literary games: Is your life Chekhovian or Shakespearian? Who would have written the story of this person: Edith Wharton or Henry James? I liked her references, such as when she discusses the relationship between Constance Woolson and Henry James, or when she speaks of an insight gained from Edmund Gosse’s Father and Son: “One is lonely for the absent idealized other, but in useful solitude I am there, keeping myself imaginative company, filling the room with proof of my own sentient being.”

I’m cherry-picking parts I especially liked. In between, there are many wonderful scenes and witty, revealing conversations, such as this one where she runs into a former lover.

“You used me!” he cried.

“Not nearly well enough,” I said.

“What was all that about anyway?” he asked wearily.

. . .

“I can’t do men,” I said.

“What the hell does that mean,” he said.

“I’m not sure.”

“When will you be sure?”

“I don’t know.”

“So what do you do in the meantime?”

“Take notes.”

If you are looking for fascinating company in your own useful solitude, try spending some time with Vivian Gornick. This brief and captivating book will set you thinking and reminiscing.

What memoir have you read recently that felt like a meeting with a longtime friend?