Recently I attended a talk about the flood of hippies and other progressives moving to Vermont in the 1970s and this book was mentioned. Having lived in a rural part of the state briefly in 1971, I was well aware of how conservative it was and so have always been curious as to how these two wildly different populations managed to coexist. Daloz’s book, subtitled Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America, helps me understand.

The story of the Myrtle Hill commune provides the narrative backbone, with digressions to describe the commune movement in the U.S. In 1970, three young people—Lorraine, Fletcher and Craig—found the 116-acre former potato farm and within a few weeks Craig had bought it, using his inheritance following his father’s sudden death for the down payment. Craig then created a land trust so it would be owned in common with everyone taking turns covering the mortgage payments.

After the group, which quickly swelled in numbers, discovered the joys of mud season in Vermont, they spent an idyllic summer living in tents, tipis and lean-tos. “It was like a weeks-long camping trip, but more romantic because this was not a mere vacation, but, for all of them, their new way of life.

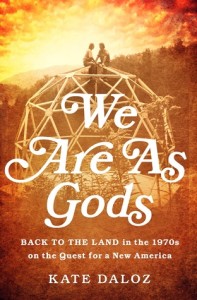

They were determined to be self-sufficient, acquiring chickens, two milk cows and a beef calf who all had to be cared for. Besides building a rough shed for the chickens, they dug an outhouse and planted a garden. Water for cooking and washing had to be hauled in five-gallon buckets in the back of Craig’s truck. Lorraine prepared meals over an open fire, while Nancy cared for the children. The group had big plans for the future—a school for the children, wind-powered generators, a radio station—but their immediate task was to build a geodesic dome for winter housing.

We also get to know their neighbors, some who were original Vermonters and some, like the author’s parents, who wanted to go back to the land but were not interested in the communal part.

As with other groups during this idealistic period, the Myrtle Hill residents had no leader, making decisions by consensus. They embraced free love and shared occasional after-dinner marijuana; their open-door policy welcomed curious hippies and others. However, as seen by the division of labor above, they had brought gender role assumptions with them. And then, of course, winter arrived.

Daloz follows the group from its idealistic beginnings through the gradual disenchantment, conveying their stories realistically yet with sympathy. Even in describing her parents’ path, her journalistic tone doesn’t waver.

It’s a fascinating book, combining the intense focus on Myrtle Hill and its neighbors with a wide-ranging summary of the counter-culture of the period, the growth and brief life of the commune movement, and the gradual recognition among the commune members that no one is actually self-sufficient. We all, including their original Vermont neighbors, rely on our community, and some jobs are full-time so are better left to someone else.

At first the book saddened me, as I remembered my own back-to-the-land dreams of the same period. But as I read on, I realised that my reasons for not eventually choosing that path had been good ones. I’d had the good fortune to work on a friend’s dairy farm for a season and quickly saw that while I enjoyed the work, such a life was not for me. The idea of writing at night when the farmwork was over turned out to be a ridiculous fantasy, for all the reasons that plagued the young people in this book.

So when I did start visiting communes thinking I might find one where I could prosper, I knew what to look for. I ended up choosing community over commune, and do not regret it. Still, this book brought back many pleasant memories and also helped me to better understand the culture in today’s Vermont.

Have you read a book that took you back to an earlier period in your life?