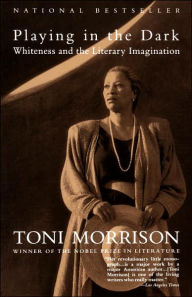

Published in 1992 but still relevant today, this work of literary criticism looks at how writers create characters different from themselves, specifically how white writers use black characters in their work. As a writer she must imagine others and, thinking about that process, she became curious as to how black characters are portrayed in the U.S. literary canon, which at the time was almost exclusively white.

Morrison also looks at the effect on the work of these white writers as they pretend that race is not a factor in their work. “What became transparent were the self-evident ways that Americans choose to talk about themselves through and within sometimes allegorical, sometimes metaphorical, but always choked representation of an Africanist presence.”

Applying this new critical approach, Morrison describes the deliberately constructed Africanist persona and how it functions in the American literary imagination, examining works by Faulkner, William Styron, Hemingway, and others.

She looks at the silence around race, for example, in Henry James’s What Maisie Knew and the lack of critical attention to the black woman who is the agent of moral choice in that novel. In Willa Cather’s story “Sapphira and the Slave Girl”, Morrison’s reading of race shows Sapphira not so much a cruel mistress as a desperate and disappointed woman whose social superiority is the only thing she has left to validate her self-image.

Examining American literature through this lens is fascinating. Morrison looks at the way authors such as Melville and Twain use the image of a slave population to investigate problems of human freedom and the fear of failure or powerlessness in white people. She shows how these authors relocate internal conflicts to slaves whose voices are silent.

These speculations have led me to wonder whether the major and championed characteristics of our national literature—individualism, masculinity, social engagement versus historical isolation; acute and ambiguous moral problematics; the thematics of innocence coupled with an obsession with figuration of death and hell—are not in fact responses to a dark, abiding signing Africanist presence. It has occurred to me that the very manner by which American literature distinguishes itself as a coherent entity exists because of this unsettled and unsettling population.

She also points out the troubling discrepancy between the fearful and haunted early American literature—Hawthorne, Poe, etc.—and the American dream of a city on a hill.

In addition to offering an allegorical foundation for major themes of American literature such as autonomy, absolute power, and freedom itself, Morrison suggests that this Africanist imagery “provided the staging ground and arena for the elaboration of the quintessential American identity.”

To me, her discussion sheds new light on today’s concerns about cultural appropriation. I am sympathetic to all sides : the writer’s need to tell the story she is passionate about, the importance of not preempting marginalized voices, and the necessity of having more diversity both in our reading and in our writers.

Have you read something or seen a lecture that gave you new insight into the books you’ve read?