I’ve been taking refuge in YA books from the depressing ugliness of some of my adult reading. This series about the Casson family started out fun. It’s a rather madcap family where the mother, flighty Eve, is too busy painting in the garden shed to feed the children, while the father Bill lives in London where he can do his “real art” without being bothered by children underfoot.

Yes, I should have know then.

However, at first it’s rather fun. As in the best MG and YA books, the children take charge. Indigo makes hearty meals to keep Caddy’s strength up while she studies for exams and takes ridiculous driving lessons. She’s a heart-stoppingly incompetent and distracted driver but her teacher , “darling Michael”, is too enamoured to care. Saffy becomes friends with the wheelchair girl who lives nearby when they have an encounter that is half a battle and half a recognition of soulmates, before hatching a daring plan to find Saffy’s inheritance.

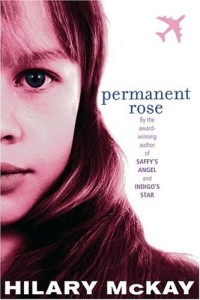

In the first book, Saffy’s Angel, we learned that the children are named after colors on the paint chart posted in the dining room: Cadmium is the oldest; then the boy Indigo, with the youngest being Permanent Rose who was so very impermanent at the time of her birth. Saffron, however, can’t find her name on the chart and thus learns that she is adopted.

My irritation with Bill grew, but what kept me reading was my fascination with Rose, a belligerent, truth-speaking child who is—through some trick of genes and chance—a born artist, more of an artist than either parent. She’s fierce in her passions and honesty, and utterly blunt in her exposé of the Casson family dynamics.

In this, the third book in the series, she writes letters to her father—“Darling Daddy,”—describing the desperate happenings at home, hoping that they will persuade him to come home, something that he has ceased doing since acquiring a new girlfriend. Bill, happy in his London life, spending the money he earns on trips to Paris and New York and on Samantha rather than on his cash-strapped family, chooses to believe that Rose is making things up.

She isn’t.

Indigo also pulled at my heartstrings. I have too often seen children bravely take up the slack and act as parents when their own irresponsible and self-indulgent parents prove useless. Sent to buy groceries—“Real food!” as one child demands—Eve returns with cherries and tubes of paint.

I know it’s all meant to be jolly fun and aren’t the children clever to manage on their own, but frankly, it’s all too real to me. I find it heart-breaking. Tempted to strangle Bill and smack Eve, I wanted—if nothing else—to call child services on the pair of them. They obviously “love” the children, but how empty is a declaration of love without a meal behind it or even just noticing that a child is struggling?

My only consolation is the other adults who step in to help the children with a meal or a timely helping hand. And the competence of the children themselves.

The theme of all these books seems to be that quirky families are far more interesting and wonderful than those boring families with regular meals and clothes and parental attention. For me, though, the only thing that matters in these stories is the love—as in care and attention—each child has for the other.

I learned long ago, when still very young myself, that “love is not some wonderful thing that you feel but some hard thing that you do.” As always, I learned that from a book, in this case one by Elizabeth Goudge. In these stories of the Casson family, I don’t see anything I would call love from the parents, only between the children. And that—the absence of parental love—seems to me a tragedy. No wonder Permanent Rose is so belligerent, demanding what she needs and brooking no denial.

Have you read a novel where you had mixed feelings about the characters and the theme?