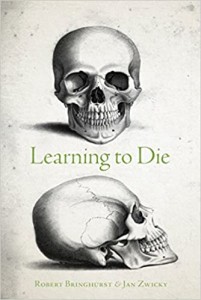

While the title of this slim volume sounds tailor-made for this pandemic with its hundreds of millions of deaths, the subtitle clarifies its theme: Wisdom in the Age of Climate Crisis. Its two essays and Afterword give us perspective on the environmental catastrophe through which we are living.

These are not attempts to quote scientific studies to persuade us of the seriousness of our Anthropocene Era, though statistics are given and backed by numerous endnoted sources. Instead, the two essays address our inner selves and how we relate to the world, while the Afterword refutes a recent book which proclaims that there is no problem because more progress will save us.

In “The Mind of the Wild” Bringhurst reminds us that life survived and regenerated after each previous global extinction event, though it wasn’t the same life as before. I can’t help but think again about our current time, when it appears our post-COVID 19 world will not ever be quite what it was before.

Bringhurst goes on to say that after the coming catastrophe, it will be the wild—defined as “everything that grows and breeds and functions without supervision or imposed control”—that “will rescue life on earth, if anything does, because nothing else can.” Humans may not survive; any that do will find their culture eviscerated.

He refers to an 1858 speech by the physicist Michael Faraday, who in a lecture on electricity said, “I am no poet, but if you think for yourselves, as I proceed, the facts will form a poem in your mind. ” He goes on:

Letting the facts form a poem in your mind is an exercise in a certain kind of thinking: letting something happen instead of forcing it to happen, and simultaneously letting yourself be enlarged. Letting the facts form a poem in your mind is a way to practise thinking like an ecosystem, thinking like a planet, thinking like a world. But in order to let the facts form a poem in your mind, you have to have some facts to start with.

And of course you must have a mind in good working order. Increasingly we have been learning that one of the best ways to get our minds in order is to go out into the natural world, the wild. Bringhurst says that there we “enter a larger, possibly stricter, moral sphere” and encourages us to bring that “heightened sense of morality” home with us.

There is much more to this moving and persuasive essay. It is reinforced and expanded by “A Ship from Delos” by Zwicky. The title comes from Plato’s account of the death of Socrates, which was delayed by the custom of not allowing any executions during the annual voyage to Delos to honor Apollo. The sight of the ship returning tells Socrates that his life will end the next day.

Zwicky says that “Humans collectively are now in Socrates’ position: the ship with the black sails has been sighted.” Building on Bringhurst’s appeal to our moral selves, she proposes the virtues that Socrates embodied, starting with awareness (attended by the humility to recognise what we don’t know).

Here it is the recognition of our own mortality, which she describes beautifully as “to look at the world openly and to see it, and one’s own actions, and the actions of others, for what they are: gestures that vanish in the air like music.” She goes through the other virtues, showing how cultivating them will serve us well as we enter our extinction event, both by perhaps postponing it a little and by giving us tools to handle it.

For the Socratic virtue usually translated as piety, she substitutes contemplative practice, saying:

At the heart of contemplative practice of any sort is attention. As [Simone] Weil observes, prayer is nothing other than absolutely unmixed attention . . . The more we attend to the world, the less we find ourselves wishing to control it.

I recommend this small book to anyone who wishes to go deeper into an understanding of who we are and who we are becoming as our culture rocks and is remade during this time of great change.

What writers help you to adjust and find your best life during difficult times?