Sometimes you start a book, and you cannot stop until you have turned the last page.

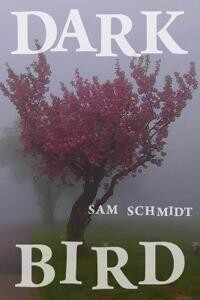

That is what happened to me reading Schmidt’s new collection of poetry. In fact, it begs to be read as a whole. It begins so innocently, with a tree—“An ordinary tree”—a tree in winter, in a graveyard across from the author’s home. A tree with a crow in it.

Of course I thought of Haworth. The first time I visited the home of the Brontë sisters, a bleak day in the dregs of winter, I was shocked to find that their front yard was actually a cemetery. The Brontë parsonage lay right up against the graveyard and, beyond it, the grey stone church, and everywhere the crows, hoarsely screaming and rising in the air at my intrusion.

These poems stand up to the comparison, even to the echoes of the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, Eleanor Farjeon, and others. The reader is pulled in, made complicit in this openness to the world as we move through the year from winter to winter. One poem begins:

A tree revolves among faces.

When I open my eyes, it’s back as it

was. It was never a god in disguise.

It won’t reveal

a passage through. An exit

out. It’s not a young

woman—or an old one—

transformed.

Everything I look for in poetry is here: language that sings, lines concise and perfect as a snowflake, themes that speak to the universal heart of human existence, and surprising images that range from fairytales to news stories. Some of the images recur, spiraling into new meaning each time they appear.

I love that these poems circle around a graveyard. Anywhere we walk is a graveyard, isn’t it? Layers of rock and older civilisations, beings that came before us. They represent the geology of time, personal time and the earth’s time.

In my review of Schmidt’s previous collection, Suburban Myths, I praised the depth of emotion and experience in his work. Here he achieves that depth partly by the brilliance of his writing and partly by the force of his themes. Even more striking is how vulnerable the author allows himself to be and, therefore, how intensely powerful each poem is. Wrestling with demons from childhood, coming to terms with a father’s criticism and your own child’s independence, navigating a decades-old marriage—the more personal the poems are, the more they open us to ourselves.

He balances between silence and speech.

Between hope that he

might talk his way

into friendship with the sky. And

despair that he’s asking too much.

These songs invite us to walk through this world bookended by graveyard and family home. We enter, not a wood, but a single tree. We bang on the doors that are shut and unearth what is buried within us.

What poetry collection have you read that you kept reading and rereading?

Disclosure of Material Connection: I received a copy of this book free from the author. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own.