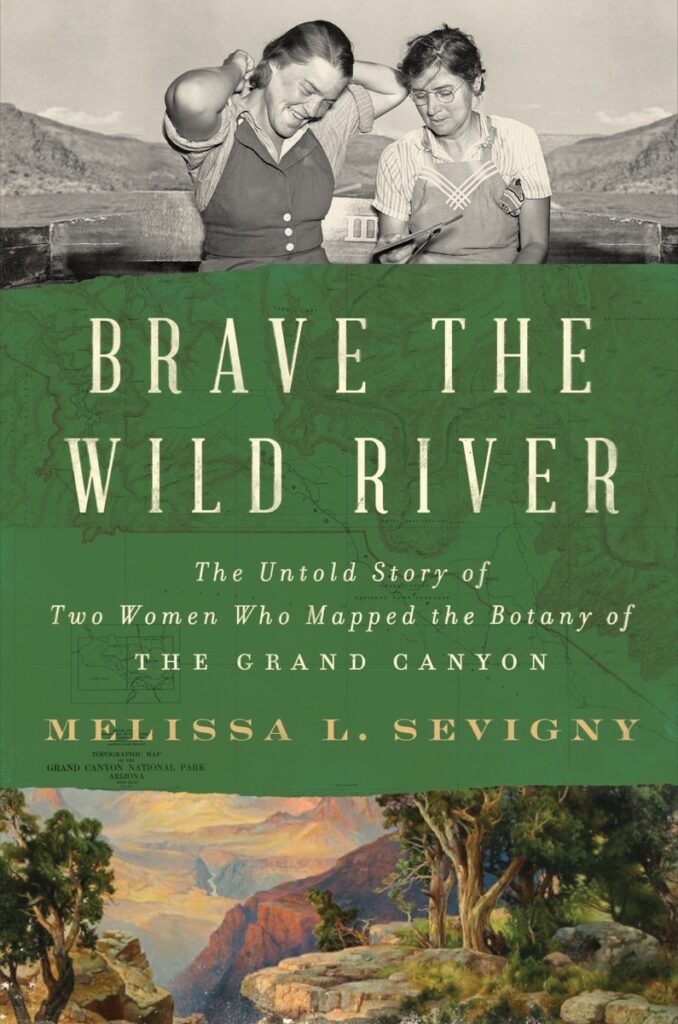

Subtitled The Untold Story of Two Women Who Mapped the Botany of the Grand Canyon, this nonfiction book rescues a story, misrepresented at the time and now forgotten by all but scientists. In 1938 botanist and University of Michigan professor Elzada Clover and her student Lois Jotter set off down the—at the time—untamed Colorado River with four men in homemade boats.

The women’s goal was to survey the plant life of the Grand Canyon for the first time. Only a very few people had ridden the Colorado—considered the most dangerous river in the world—through the Grand Canyon and survived. The media, of course, went wild over the idea of women going on such an expedition, and throughout the entire experience concentrated on their clothes and appearance, without mentioning botany or the women’s work.

Drawing on the journals of Clover, Jotter and three of the men, as well as her own background as a science journalist, Sevigny has created a thrilling and very human story of these two women and their accomplishments, which botanists and ecologists still rely on today. She brings to life the sensation of entering each new section of the river: the rapids, the soaring stone walls, the way storm clouds seem to boil down into canyons.

The interactions between the group are touched on lightly: the inevitable irritations, the teasing, and the mutual support and little kindnesses that carry the day. While the story concentrates on Clover and Jotter’s experience, the others are presented as well, especially the expedition leader Norman Nevills and Buzz Holmstrom (who did not travel with them).

Holmstrom was one of the few who had run the river and survived and, on hearing of the projected expedition, famously said, “Women . . . do not belong in the Canyon of the Colorado.” However, he came to respect and support Clover and Jotter. He followed their journey and, when possible, provided assistance. Afterwards, he was the only person Clover could talk with about how much she missed the river.

The author also slips in bits of background as needed. Much of the science we take for granted today was still in flux, such as evolution, the great age of the Earth, or the idea that plants or animals could become extinct. Continental drift was first proposed in 1912 was still considered nonsense. Geologists “did not yet believe land masses could unmoor themselves and go rollicking around the planet like bumper cars.”

Sevigny brings out the different ways plant life was being categorized and understood at the time, such as the idea that “plant communities advanced through stages of development to a final, stable stage, which might be forest, prairie, tundra or desert, depending on the region’s climate.” This culmination of this process—called succession—was thought to be a “climax community” which would then never change again. Of course, we see today how that explanation is insufficient, but Clover and Jotter were among the first to advocate a systems approach—what we understand as ecology today.

This is a gorgeous story of courage and camaraderie. Whether you’re looking for a thrilling adventure, an immersion in a strange and beautiful landscape, or a forgotten piece of women’s history, this is a great read.

Can you recommend a narrative nonfiction book about a forgotten piece of history?