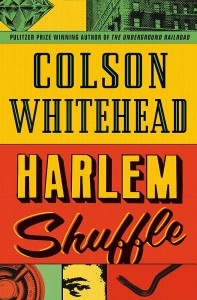

While all Colson Whitehead’s novels are well-written, their subjects and genres vary widely, much as Graham Greene wrote literary novels like The Power and the Glory and what he called “entertainments.” After The Underground Railroad and the wrenching Nickel Boys, Whitehead seems ready for something a bit lighter. Harlem Shuffle is entertaining, for sure, with serious undertones.

Ray owns a used furniture store in late 1950s and early 1960s Harlem. He’s always on the alert for an angle, milking his network of friends and contacts for deals like trading an outdated radio for a used television. The son of a legendary gang leader, Ray wants to play it straight; as we learn in the book’s first line: “Ray Carney was only slightly bent when it came to being crooked.”

So he turns away the serious capers he’s offered a part in and concentrates on making his business a success, hard as that is for a Black man in mid-twentieth century America. He wants a better life for his wife and children and that takes money. And it means he has to keep his nose clean, not be like his father. Adding to the stakes for Ray, his in-laws never let him forget that he is not good enough for their daughter.

But he has this nephew. Ray feels responsible for Freddie who keeps getting into trouble, finally getting in deep enough to call on Ray for help, endangering both of them. Thanks to his father, though, Ray knows who to call on for backup. He’s also adept at navigating the treacherous waters of Harlem’s dual economy, the one that’s above-board and the one that isn’t. Of course, as in any life, race is always a factor in Ray’s dealings with others, explicitly or implicitly.

It’s a light story on a serious theme: Is breaking the law the only way to lift yourself and your family out of poverty? One thing that struck me, reading Ray’s story, was just how easy it is to slip into a pattern of minor grift, no matter what your race or socio-economic status. Do a favor for a friend, bend the rules a little to help someone out, and there you are: on the other side of the line. You may say, I’d never fence stolen goods, but it’s only a matter of degree.

While some in my book club were disappointed that the story wasn’t as weighty as The Nickel Boys, we were all entertained. We liked the elaborate schemes Ray comes up with to get Freddie and himself out of trouble or to revenge a slight. I was especially amused by Ray’s rhapsodies about furniture: memorising the ad copy for a new line of furniture or appreciating the details of a particular recliner.

One person noted that we get to see the softer side of people who in other stories might just be stereotypical thugs or prostitutes. One assassin-for-hire dreams of owning a farm someday, while a kept woman turns out to have an extraordinary sense of drama and design. I appreciated the care taken to fill in even the minor characters, though several of us still had trouble keeping them straight. The few women play very minor roles in the book; I guess that too is true for someone like Ray in that time and place.

Through the three time periods of the novel, we see Ray drawn deeper into the life he’d sworn to avoid, betrayed by his love for his family and his loyalty to Freddie. I admire the structure of the novel: the three sections, the pacing, the well-spaced turning points, and the resonance between the heists at the beginning and at the end.

One member of my book club was surprised that the “heist” parts weren’t more suspenseful, as in some of the heist movies we’ve seen. I, on the other hand, enjoyed the measured unfolding of Ray’s plans, his ingenuity and resilience. In this “entertainment,” Whitehead has given us a slice of life: realistic characters responding to real-life challenges.

What is your reaction when a favorite writer switches between genres from one book to another?