Seven-year-old Tolly’s father and stepmother are in Burma, so he usually spends holidays at his boarding school. However, this December he’s off to live with the great-grandmother he’s never met, traveling by train through flooded fields in East Anglia. An imaginative child, he wishes it were the Flood and his destination the Ark.

He’s not far wrong. After a perilous journey by taxi through the watery landscape, Tolly—his full name is Toseland—is saved from having to swim to the house by the arrival of Mr. Boggis in a rowboat. The house, originally known as Green Knowe, is now called Green Noah. Tolly’s family has lived there for over 300 years, and there has always been a Mr. Boggis who works there.

The room seemed to be the ground floor of a castle, much like the ruined castles that he had explored on school picnics, only this was not a ruin. It looked as if it never possibly could be. Its thick stone walls were strong, warm and lively. It was furnished with comfortable, polished old-fashioned things as though living in castles was quite ordinary. Toseland stood just inside the door and felt it must be a dream.

While his great-grandmother is immensely old, she hasn’t lost that sense of the mysterious world that flickers just behind our ordinary surroundings. She tells Tolly of three children who used to live there in the 17th century, teaches him to summon the birds, and inspires him to listen for the hoofbeats of the great horse Feste who belonged to one of the children.

Lucy Boston wrote this delightful middle-grade story for her own enjoyment after she bought a home in 1939 in Cambridgeshire. As she restored the house and gardens, they became the setting for this story and four others. Lucy’s daughter-in-law now lives at the Manor at Hemingford Grey, and opens the garden to visitors year-round, while tours of the house are available by appointment.

Encountering this tale for the first time is an enchantment of its own. Slowly, ever so slowly, the other world begins to manifest itself: a marble rolls across the floor of its own accord, voices seem to whisper in the garden, sugar lumps disappear from the ancient manger in Feste’s stall. Reading it, I felt like a child again, the child I once was, who believed it was just possible that maybe that shadow in the trees was actually . . .

After thoroughly enjoying the book, I came back to it as a writer, appreciating the way moments of magic creep up on the reader until the entire story seems perfectly plausible. Tolly’s adventures are punctuated by his great-grandmother’s tales of each of the children, the statue in the garden, the topiary creatures in the garden, and so much more.

Similarly, the author balances and metes out the scary side of magic, from Tolly’s anxiety at the very real flooding at the beginning, through the tingle of fear that edges each fleeting magical moment—how can this be real? And how to hang onto it?—to where terror begins to creep in.

I loved the way the house and stables and gardens are used, their realistic details enchanting in a more mundane sense. And Boston uses the natural world throughout in an unforced way to create mood and theme and adventure, not just the gardens, but floods and snow and birds. Remarkable.

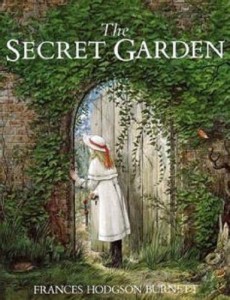

I wish I’d read this as a child. First published in 1954, it is of a piece with others books I loved then, like The Secret Garden and The Diamond in the Window. Now I have to try to find the other four Green Knowe books.

The books we read in childhood often stay with us. What magical story from childhood do you remember in this season?