In this retelling of Peter Pan, Wendy Darling lives in Astoria, Oregon, a small town where children have begun disappearing. People turn to her because she and her brothers also went missing five years earlier. She has no answers because when she did turn up in the woods, she remembered nothing of what happened. Michael and John have never returned.

When Wendy, on her eighteenth birthday, almost runs over a boy lying in the middle of a forest road, she discovers that the Peter Pan of the childhood stories her mother told them is real. He’s left Neverland to recruit Wendy’s help in finding the missing children.

It’s clear that Thomas put a lot of thought and imagination into how to adapt the magic of the J.M. Barrie original to the modern world. I especially like how he characterises the antagonist. Also, he’s done a good job of understanding issues such as grief, guilt, and PTSD. The damage to the Darling family, in particular, struck me as genuine.

Unfortunately, I came near to setting it aside unfinished, despite so much I liked about it and my own fascination with Peter Pan. Only the fact that I was listening to it as an audiobook while doing chores and commuting enabled me to stay with it. So what lessons can I as a writer draw from this Young Adult novel and NYT bestseller?

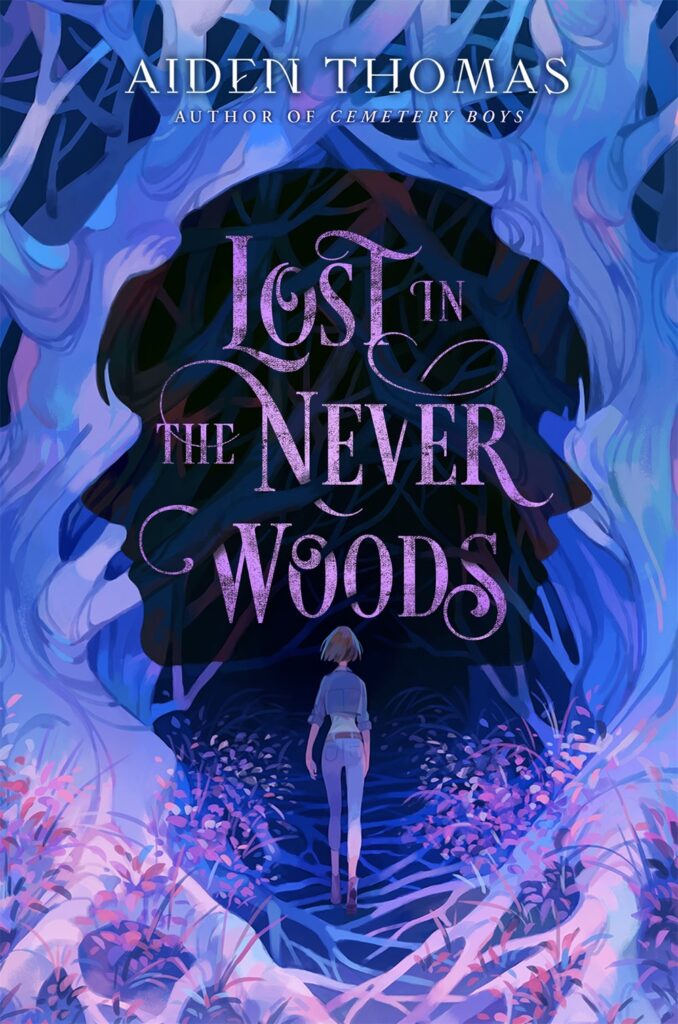

Go for broke with the cover. The book’s cover is fabulous! It draws you in to the tangled woods with their tempting flowery path and threatening blue and mauve trees. And the mysterious faces in silhouette. Who wouldn’t want to pick up a book with a cover like this?

Take time to describe your main characters with surprising sensory details. The early descriptions of Peter charmed me, with so many wonderful details such as twigs in his hair, the woodsy scents that accompany him, the oddball clothes that he’s picked up in Wendy’s world. I loved this aspect of the story.

Make sure your characters feel like real people. Sadly, after the wonderful description of Peter, he and Wendy, not to mention her family and best friend, come across as one-note characters. This is especially problematic with Wendy, since she is our point-of-view character.

Vary your pacing. The whole story is at fight-or-flight level. Wendy starts the story freaking out and, aside from one or two brief moments of connection, she spends the entire story at the same panicked level. Many Goodreads reviewers complained about slow pacing. I attribute this reaction to the pedal-to-the-metal emotional level, the absence of character development, and the scarcity of actual actions Wendy and Peter take to solve the problem.

These problems could be attributed to a rush to publish a second novel in 2021 after the big success of Thomas’s debut novel Cemetery Boys in 2020. Most writers labor for years on their first novel trying to make it perfect in this difficult marketplace. Then the follow-up doesn’t have a chance to get as much attention.

I’m impressed by Thomas’s productivity. I’m also taking a lesson from the way he interacts with his fans online, from his fun bio to the way he addresses them directly. Given the very positive reviews for Cemetery Boys, I will give that one a try. I’m also looking forward to seeing how this promising writer develops over his next few books.

What Young Adult book laced with a bit of magic have you enjoyed?