I was first alerted to Hauser’s essay “The Crane Wife” by the Longreads list of best essays in 2019 which sent me to the Paris Review where it was published. I thought it brilliant.

So I looked forward to reading this book. Hauser calls it “a work of personal nonfiction,” saying “These essays reflect my life as I remember it and the stories I’ve made of that life to understand how to keep living in it.”

In “The Crane Wife” Hauser goes to Texas to study the whooping crane shortly after calling off her engagement. Sections alternate between her engagement and her experience with the cranes. Equally important are those who study the cranes, the motley collection of volunteers who welcome her to this Earthwatch event.

She gives a poignant recounting of her deteriorating relationship, constantly setting aside her own needs as shameful. Men are entitled to have needs, but “when a woman needs, she is needy.” At the same time she is measuring the small things that fill the needs of these whooping cranes who are on the verge of extinction.

The Crane Wife is a story from Japanese folklore about a crane who fell in love with a human man. She didn’t want him to know she was a crane, so every night she plucked out all of her feathers. “Every morning, the crane-wife is exhausted, but she is a woman again. To keep becoming a woman is so much self-erasing work.”

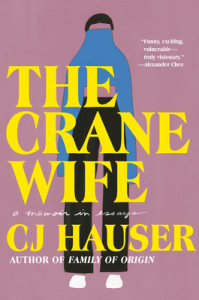

I found the book’s cover image disconcerting: a person, presumably a woman though not obviously, whose turtleneck is pulled up to erase her face, leaving her vulnerable stomach bare. I suppose it’s meant to refer to the title essay and Hauser’s erasure of herself, but it doesn’t reflect the collection and ultimately felt demeaning.

What makes these essays so good is the way she balances personal stories with those of others, sometimes her friends, sometimes a story’s characters, sometimes both. I especially enjoyed her bookish roamings through Rebecca and Shirley Jackson’s oeuvre. I also liked her travails in deciding what to say when asked to officiate at her friends’ wedding, wanting to capture the breadth and depth of the women’s relationship, while also discussing her obsession with The X Files and what she calls its MSR: Mulder-Scully Relationship.

Another reason these essays are so absorbing is her use of specific details, like shopping for nylon hiking pants that zipped off at the knee, and incisive incidents like a bit about Christmas stockings. Mostly, though, it is her openness that makes these essays hit home, her willingness to be vulnerable.

Many of them have to do with her love life, which I would have found more interesting thirty years ago. Still, I enjoyed them and even listened to the entire collection twice. It is read by the author, whose voice has a bubble of laughter under it, even during the sad parts, keeping me a little off balance, which is not a bad thing.

Near the end of the book she returns to the idea of the stories we tell ourselves about the events of our lives, stepping back from the story to comment on her authorial choices. This is a smart book and gave me a lot to think about.

What essay or essays would you put on your best-of-this-year list?