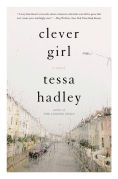

I like to read stories about ordinary lives, so I looked forward to this novel by Tessa Hadley. In ten discrete chapters, we experience the life of an ordinary Englishwoman named Stella from childhood to middle age. Written in the first person, we see Stella’s life as she sees it: her experience of the events of the last half of the 20th century.

Hadley beautifully captures what life was like during that turbulent time: we get Stella’s teenaged rebellion of embracing punk culture with her androgynous boyfriend Valentine, and later her avoiding the arguments about politics in her commune, and so on to the end of the century. Hadley also shines at using quick, precise details to capture a person, place or thing. When she finds buttons at an old bombsite, they are “a coral rose, wooden toggles, a diamanté buckle, big yellow bone squares, toggles made of bamboo.” Of Stella’s grandmother, she says:

She bought her clothes from the children’s department (cheaper), and went to the hairdresser’s every week to have her hair set in skimpy grey-brown rolls pinned to her scalp: not out of vanity, but as if it was her duty to submit to this punishing routine.

As writers, we’re told that the first page of your novel should not only grab the reader but also introduce the main character, the time and place, the main character’s goal, and a hint at who or what might stand in the way of achieving it. Looking at this novel’s first page, we can confidently check off a few items. Our narrator is a child living alone with her mother in the 1950s and early 1960s, though only later do we find out they are in Bristol. She and her mother get along well, sharing the same tastes.

The first paragraph is about Stella’s missing father, “unpoetically” named Bert. Her mother says that he is dead but in the same sentence we are told that “I only found out years later that he’d left, walked out when I was eighteen months old.” As it turns out, this undercutting of Stella’s present-day experience by the interjection of knowledge acquired in the future will continue throughout the book. As a result, there is little suspense. We know, for example, who will die before the scene plays out.

Another aspect of this paragraph gave me a qualm. It seems to indicate that the book is going to be about how Stella’s life is shaped by a man. Sadly, that turns out to be true. Each chapter is focused on a man who changes Stella’s life. The only references to the women’s movement of the seventies come from an intense lesbian at Stella’s commune.

What about Stella’s goal? A structural difficulty with starting the book with her as a child is that children rarely can articulate a goal that will carry through their lives into middle-age, but even within each chapter she doesn’t seem to have a goal. We have the clue of the title. There is this sentence on the first page about her father having absconded rather than died: “I should have guessed this—should have seen the signs, or the absence of them.” From these slight tokens, I guessed that Stella’s goal through the book would be to grow into her cleverness. Accurate enough, as it turns out, though references to it are few and overwhelmed by the drama of deaths and dirty dishes and diaper pails. The rare times she mentions something related to her emerging intelligence (“cleverness” is pejorative and somewhat demeaning to me, but means something different in England) I began to be interested, but it didn’t last long.

The book would have been a lot stronger if this goal—or any purpose on Stella’s part—had been sharpened and used to tie the incidents together. Without it, the book is not so much a story as a hodgepodge of happenings.

For what might stand in her way, we have this sentence about things that were powerful at that time: “shame, and secrecy, and the fear that other people would worm themselves into your weaknesses, and that their knowledge of how you had lapsed or failed would eat you from the inside.” As it turns out, what stands in her way are her abrupt changes of direction, the consequences of her decisions or more often non-decisions. I can see where these could be a result of that fear. She even says at one point that “I couldn’t bear the idea of being exposed in my raw, unfinished ignorance.” Even at the end she says, “I still feel sometimes as if I’m running away, escaping from something coming up behind me.”

I’m confident that Stella’s fears, sudden changes of direction, and concealed cleverness, not to mention her way of letting men define her life, accurately reflect the lives of many women. However, I found myself observing her from a distance; I did not care what happened to her. Perhaps that’s because I found little to admire in her. And oddly, she always fell on her feet. As a single mother myself, I found it unrealistic that she always found someone willing to take care of her and her children.

Other roadblocks also magically melted away: for example, she suffered no teenaged angst because she had the perfect boyfriend; the woman who learned her husband was having an affair with Stella immediately volunteered to give him up so they could be happy; plus the wife’s children showed no resentment towards Stella for breaking up their family. Since Stella didn’t have to struggle to overcome her obstacles, the story lacked drama and I couldn’t muster any concern for her.

The lack of suspense bored me. Things certainly happened to her (She says, “I thought that the substantial outward things that happened to people were more mysterious really than all the invisible turmoil of the inner life.”), but without any buildup to them, there was no tension. She would also change direction with no warning, such as when from one sentence to the next she loses interest in the university degree she’d spent pages acquiring and heads off in another path. Without foreshadowing or dramatic tension, these events coming from out of the blue don’t create the kind of narrative I expect from a novel. The book feels like a random collection of incidents. Life can be like that, but it doesn’t make for an interesting book.

One friend who liked the book a lot said that it was the story of a person who floated through life, letting things happen to her, and didn’t live up to her potential. She added that it was an important book because many people don’t live up to her potential. That may be true, but doesn’t make it a compelling story. Another friend pointed out that nothing that happened to Stella changed her; she didn’t grow or become wiser, so she still sounded child-like as she aged.

I don’t mean to be overly negative. There are many things to like about this book: the novel-in-stories aspect, the evocative images and wordplay, the recognition when you stumble across things from your own past. One friend said that recognising so many incidents made her feel as though she were reading the story of her own life. Adding something to be achieved and suspense over how that might happen would make this an excellent novel. Even an ordinary life can be a good story.

What does the first page of the novel you are reading tell you about the rest of the book?