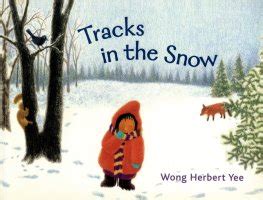

I’ve been reading a lot of picture books lately since I’ve been babysitting for a two-year-old. We’ve both fallen in love with this one. It starts with a child looking out the window at the snow and wondering what made the tracks there, and where the tracks go.

They (I’m deliberately using the plural because the child is not named and is not obviously a particular gender—part of the book’s charm) put on boots, coat and mittens (a skill my young friend has been working on recently) and go outside.

Following the tracks, the child wanders through typical landmarks for a little one: a garden gate, woods, some rocks and over a small footbridge. As they meander, they are shadowed by various animals: a squirrel, rabbit, fox, deer. The child considers what could have made the tracks: a duck? a woodchuck? a hippopotamus?

As you might have guessed, they follow the tracks all the way back to their own house and realise they themselves made these tracks the previous day.

This is a quiet book, like the snow’s hush, full of curiosity and imagination. The gentle illustrations are minimal, almost suggestions, yet they capture a child’s body language beautifully. Being snowy landscapes, of course there’s lots of white space.

In my opinion, the best picture books tell a story and, indeed, even in this brief text we have a full story. The protagonist is the child; the problem is to solve the mystery of the tracks. The antagonist is more abstract: ignorance, what we don’t know, the impenetrability of the world.

I remember as a preschooler being terrified by the vast sea of things I didn’t know. I knew my house and yard. I knew my block, more or less. But everything beyond that was a blank, simply inscrutable. For all I knew, there could be dragons. If I wandered off my block, how would I find my way back home?

Solving these mysteries, mapping out the nearby streets a little at a time, became my ambition. I think it’s partly why I enjoyed being a mechanic and then an engineer: understanding how cars and computers work. I never liked black boxes, those enigmatic spots in a flowchart labeled “Here the magic happens”.

So in this brief tale, I see not only an outward journey for our protagonist—following the tracks, answering the question—but an inner journey to satisfy that yearning to explore the world and begin to comprehend its mysteries.

What picture book have you read that you particularly enjoyed?