The narrator wakes from a nap to find herself alone. She’s visiting family members at their hunting lodge on the edge of the Alps, and they have gone into town, leaving her with their dog Lynx. She walks down the road to meet them, but both she and the dog run into an invisible wall that separates them from the rest of the world.

Worse, the rest of the world is dead. Something has happened to kill the people and creatures on the other side of the wall. The one man she can see sitting on a bench outside a cottage never moves, nor does his body deteriorate. Eventually it falls over and is covered by vines. Same with the cows lying in the field, the dog on the doorstep.

This is her journal.

She begins writing two years into her isolated existence. Like Mark Watney in The Martian, she must “science the shit out of this” except that her science is that of the last 12,000 years: how to grow enough food to live using only hand tools and the few items in the hunting lodge.

It is her worst nightmare come true:

As a child I had always suffered from the foolish fear that everything I could see disappeared as soon as I turned my back on it. No amount of reason could completely banish that fear. At school I would think about my parents’ house and suddenly I would be able to see nothing but a big, empty patch where it had previously stood.

I’m reminded of the recurrent nightmares my sister and I had when young about a nuclear bomb falling while we were at school. Not surprising given our post-Hiroshima, Bay of Pigs childhood.

I was mesmerized by this woman’s narrative. It is fascinating to watch a society woman learn to chop wood, milk the cow she discovers on her side of the wall, scythe and gather grass for hay, and force herself to go hungry while saving back beans and potatoes to plant in the coming year. Frequently exhausted, she forces herself to keep going because the animals—the dog and cow and a stray cat—have come to depend on her.

The changes in her are subtle. Sometimes she reflects on her previous life, looking for what writers call the through-line. Worrying about the animals, she says:

I’ve suffered from anxieties like these as far back as I can remember, and I will suffer from them as long as any creature is entrusted to me. Sometimes, long before the wall existed, I wished I was dead, so that I could finally cast off my burden. I always kept quiet about this heavy load; a man wouldn’t have understood, and the women felt exactly the same way I did. And so we preferred to chat about clothes, friends, and the theatre and laugh, keeping out secret, consuming worry in our eyes.

Her grown children are on the other side of the wall. There is nothing she can do for them. There is no future beyond her own life.

One day I shall no longer exist, and no one will cut the meadow, the thickets will encroach upon it, and later the forest will push as far as the wall and win back the land that man has stolen from it. Sometimes my thoughts grow confused, and it is as if the forest has put down roots in me, and is thinking the old, eternal thoughts with my brain. And the forest doesn’t want human beings to come back.

I’m reminded of the summer I lived in a tent in the woods with a friend and her children in a second tent. Life was simple. Keep the tent clean, gather blueberries in the woods, fix the many meals preschoolers require, clean up, entertain the children. My brain did begin to rewire itself that summer.

The narrator says:

I was no longer in search of a meaning to make my life more bearable. That kind of desire struck me as being almost presumptuous . . . I’d spent most of my life struggling with daily human concerns. Now that I had barely anything left, I could sit in peace on the bench and watch the stars dancing against the black firmament.

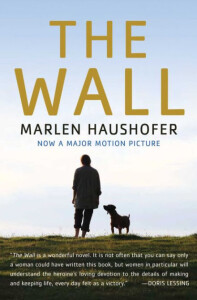

Doris Lessing said of this book, first published in 1968 in Germany, “women in particular will understand the heroine’s loving devotion to the details of making and keeping life, every day felt as a victory.” I urge you all to read it, regardless of your gender. Read it partly for the occasional insights, partly for the saga of survival, partly for the companionship of the animals, partly for the critique of our human society, mostly for the spellbinding prose.

What novel have you read that you want to immediately urge everyone you know to read?