“How very odd it must be, living at the mercy of the tide.”

Eris is a tidal island off the coast of Scotland, meaning that it can only be accessed at low tide. It is a place of crashing seas, wild storms, and dark woods where mainlanders once buried their dead to keep wolves from disturbing them.

Once the home of the reclusive artist Vanessa Chapman, now—five years after her death—the island’s only inhabitant is Grace, her friend and companion. However, Vanessa’s art and papers were left, not to Grace, but to the Fairburn Foundation run by Vanessa’s lover-turned-enemy Douglas Lennox, who feuded with Grace for years, certain that she was holding back art and papers. He is now dead, shot in a hunting accident, and his son Sebastian in charge.

When one of Vanessa’s pieces, on loan to Tate Modern, is discovered to contain a human bone, Sebastian sends James Becker, curator of the Chapman collection to Eris to gather any papers that may shed light on the origin of the piece. Becker intends—unlike Sebastian’s family—to be conciliatory toward Grace, while she initially defends her isolation but gradually finds Becker eases her loneliness.

The shifting ground between the two of them captured and kept my attention.I found myself eager to get back to the book every time I set it down, wanting to explore the twists in the plot, rummage through the complicated relationships between the characters, and measure the reliability of each person. In a time when we are told so many lies, looking for the truth becomes a skill to be honed.

While two of the story’s voices are those of Grace, who loved her, and Becker who wrote his thesis on her work and is still obsessed with her, it is Vanessa—the third voice—who is at the heart of this story. A creative woman who fled domesticity and came to this wild island, her journal entries throughout the book bring out her voice and her rage to be free.

Through Vanessa’s own words, as well as those of Becker and others, her paintings became so vivid in my mind that I could almost swear I’ve seen them. I enjoyed imagining them and can easily say that it would have been worth reading the book solely for them.

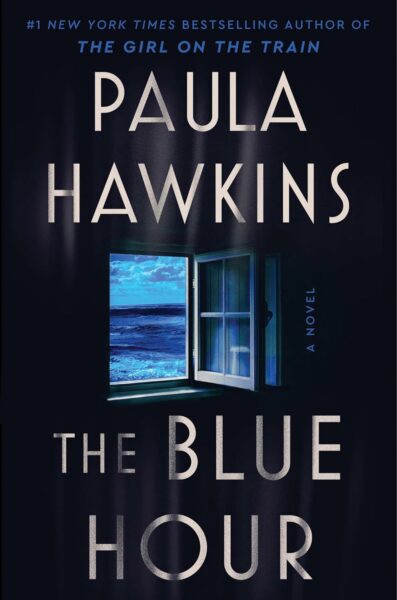

The title also drew my attention, as I have always loved that mysterious hour before sunrise and after sunset. The image signaled to me that this would not be a breakneck thriller like Hawkins’s The Girl on the Train. Instead, it’s a slow burn of buried secrets, sinister suspicions, and mysterious deaths. It reminded me of Daphne du Maurier’s novels.

A glimpse at some of the reviews on Goodreads reveals a widespread dissatisfaction with the ending. I won’t give it away, but my interpretation of it is quite different from most people’s. I like ambiguity in fiction. I like being asked to invest some of my attention into working out the subtext of a story. Here, I felt quite certain of what was being said between the lines, and am surprised to find myself at odds with so many others. I’ll say no more, but once you’ve read the book, I’d be happy to share views on the ending.

Can you recommend a mystery about a woman artist?