In this 1980 novella, the narrator revisits an incident in his past—1921 in rural Illinois, to be exact—in which tenant farmer Lloyd Wilson is murdered by his neighbor Clarence Smith. The grisly story has stayed with the narrator because he briefly became friends with the murderer’s 13-year-old son Cletus.

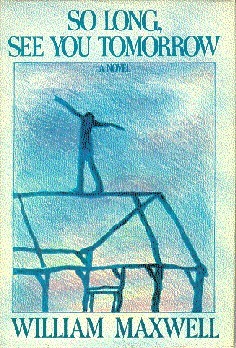

At the time, the two children encountered each other in the skeleton of the new home being built by the narrator’s father and began playing together. Not surpisingly, they never spoke of their lives outside of that space: the death of the narrator’s mother three years earlier and his father’s subsequent remarriage, or whatever tensions gripped Cletus’s family. Now, many years later, the narrator tries to reconstruct that boy’s home life, the relationship between Cletus’s father and Wilson that led to tragedy, and the narrator’s own involvement.

Smith and Wilson had once been the best of friends, helping each other out with farm work, spending long hours chewing the fat. Until Lloyd became infatuated with Clarence’s dissatisfied wife Fern, forcing his own furious wife Marie to decamp with the children. A Catholic, she refused to divorce Lloyd.

A not uncommon story, here brought to ferocious life by Maxwell’s measured prose. A contradiction, yes, and a tour de force. For one thing, the novella is pure narration—anathema these days when readers, trained by television and film, expect one dramatic scene after another. This choice, and Maxwell’s extreme emotional reserve, give the story a certain bleakness. Yet there was plenty of suspense to keep me turning the pages.

We start with the narrator’s brief memory of a gravel pit where he used to play as a child and quickly pivot—“One winter morning shortly before daybreak, three men loading gravel there heard what sounded like a pistol shot”—to a straightforward account of the crime, drawn from testimony at the inquest.

The novella continues to move back and forth between the two stories: that of the murder and that of the narrator as a boy. It also alternates between two characters: the boy who has little experience beyond his own losses and the adult narrator who knows so much more. Meghan O’Rourke calls this a “palimpsest narrator” who conveys both timelines: “two authentic, but possibly contradictory perspectives.”

That movement and the tension it creates is similar to what I find in reading a braided story that moves back and forth between two timelines, often found in historical fiction. There’s a built-in cliffhanger each time the story shifts, a pause is one timeline while we visit the other. It happens again when we shift back.

Another source of suspense in this quiet story is the unreliability of memory and of the narratives we create of our past. “Who believes children,” the narrator asks on the second page. Throughout the story, his memories are held up for examination. He also tells us frankly that he is using his imagination to fill in the gaps in his knowledge of Cletus’s life.

Much of the novella is apparently drawn from Maxwell’s own life. Fiction editor of the New Yorker from 1936-1975, Maxwell said in an interview in the Paris Review (“The Art of Fiction # 71”): “I felt that in this century the first person narrator has to be a character and not just a narrative device. So I used myself as the ‘I’ and the result was two stories, Cletus Smith’s and my own.” I’m a bit suspicious of autofiction, a term for fiction with a strong autobiographical foundation, coined by novelist Serge Doubrovsky in 1977, but I appreciate that the author here makes it clear all along that many of the details are imagined.

Memories, regrets, the summing up of our past: these are tasks common to those of us in the latter phases of life. For me, the emotional restraint, the bleakness, the effort to imagine what we cannot know—and the regrets—are familiar and gave this novella a surprising power. We never know when we wave goodbye to a friend if we will actually see them again or, indeed, if we truly know them—or ourselves—at all.

Have you read anything by William Maxwell? What did you think of it?