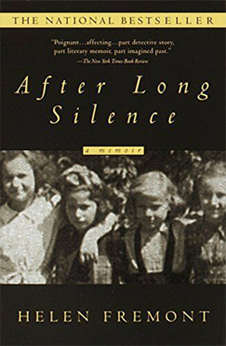

In this 1999 memoir, Helen Fremont recounts her discovery at thirty-five that everything she thought she knew about her family was wrong. Raised Roman Catholic in a small midwestern town, she knew that her parents had emigrated from Poland, but they rarely spoke about the war or the death of their own parents. Only as an adult, practicing law in Boston, did she discover that her parents were in fact Jewish and Holocaust survivors.

What a sense of betrayal, to find that your parents have been lying to you all of your life. She and her sister Lara want to know more, which sends them digging for tiny scraps of information, following threads that they could begin to weave into the story of the past. The secrets they uncover are appalling.

Their father Kovik spent six years in the Soviet gulag, thinking that the woman he’d fallen in love with back in Poland—Batya—must be either dead or have forgotten him. Meanwhile, she was trying to save her parents as they all suffered starvation and abuse. She eventually relents enough to tell her daughter the story of one pogrom, in the courtyard of her own grade school.

The story moves back and forth between the present and the past, as we discover her parents’ live as she does. I love the Author’s Note at the beginning, because with a memoir it’s important to be honest with your readers about how much your imagination is filling in the gaps.

This is a work of nonfiction. I have changed the names, locations, and identifying characteristics of a number of individuals in order to protect their privacy. In some instances, I have imagined details in an effort to convey the emotional truths of my family’s experiences.

Later she writes about her doubts about the information they’ve pried out of their mother.

I wondered about everything now. The more I knew the more I wondered. If you open one door, a thousand other doors creak open. At least, there were two of us, Lara and I, tiptoeing through this wobbly past, doused with the blood of relatives we only now were getting to know. Lara gave me the courage to face our parents and our past.

In the memoir classes I teach, people often ask about revealing things that hurt others. We are not the only people in our memoirs. Here, Fremont’s parents resist being outed as Jewish. No wonder, when that identity meant terror and torture and death.

My own parents, with a surname that could be thought Jewish, did everything they could to make sure everyone knew they were not. It could have been prejudice, but the reason they gave me was that they wanted to protect us children from what they had seen while serving in World War II. If they were still alive today, they would be horrified by the current threats to create concentration camps here in the U.S. Perhaps they’d derive some satisfaction from saying I told you so.

Kovik’s and Batya’s escapes from the gulag and occupied Poland respectively make for thrilling reading. It’s no surprise they wanted to put those desperate and traumatic years behind them and pose as an ordinary Catholic couple. Was Fremont wrong to write this book and reveal their secrets? Judging from her sequel, the book caused them terrible pain. True, the main thread is her story of discovery, yet much of the content recounts the lives of her parents. If nothing else, this story shows the way secrets held too long fester and damage our most precious ties.

Can you recommend a memoir in which family secrets surface and cause big trouble?