At 73, Julius Herz has spent his life obeying others. In his youth, he paid court to spoiled, flighty Fanny, but believed her correct in disdaining him. When his family fled Nazi Germany, they were set up in a London flat by Ostrakov, apparently a connection of some relative. He went on to give Herz’s father a job in a record shop, part of his empire.

As with Vivian’s daughters in On the Rooftop, Herz was controlled by his parents, ordered to work in the record shop and to live with them, even after his marriage, which of course quickly foundered. His parents continued to ignore him, though, and never acknowledged what Herz did for them. His brother Freddy, a violin prodigy as a youth, and the focus of his parents’ attention and ambition, suffered a breakdown after arriving in England, and spent the rest of his life in care.

Now his parents and Freddy are dead, and Ostrakov has decided to sell the record shop and the flat. Still the benefactor though, he gives the proceeds to Herz, enabling him to purchase a small flat and live simply but comfortably. Without the welcome routine of work, Herz wonders how to fill his days, usually falling back on “a newspaper and the supermarket in the morning, and in the afternoon a bookshop or gallery.” Regarding a photo of himself with a rare smile, he thinks:

Even the smile had become modified with age. The smiling boy had become a polite adult; the smile now had something dutiful about it as if it were expected of him; he would continue to offer it but without conviction. It was a smile that no longer expressed eagerness but was a suitable feature in his dealing with others. Preparing to listen, to sympathize, he would acknowledge the return of his habitual smile, while all the time registering his lack of joy.

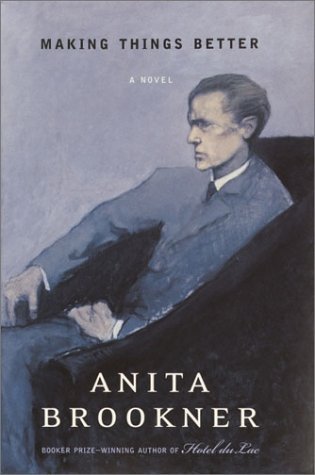

I was especially charmed by the cover, which I recognised immediately as a Romaine Brooks painting. The quiet colors disrupted by strong diagonals match the tone of the book brilliantly.

My library adds a sheet to the back flap of books where readers can rate the book and add a comment. From these, I’ve learned that Brookner’s novels are not for everyone. You couldn’t call them fast-paced: because they are so internal to the protagonist, there is a preponderance of narration.

For me, much of their value lies in the deep dive into the psychology of a silent person. By that I mean someone who for whatever reason—introversion, social anxiety, solitude, learned behavior—does not interact much with others. They aren’t the ones who bend your ear about their latest love affair over a bottle of wine. They are not the ones who play tennis or join a book club.

The lack of interaction leads to fewer of the dramatic scenes that make up the bulk of most modern novels. Teachers of fiction and creative nonfiction (including me) emphasize that modern readers, accustomed to film and television dramas, expect a story to be mostly dramatic scenes with a little narration as necessary. Some readers have gone on record that they automatically skip over descriptions of a place or a person to get to the action.

Here the scenes are internal and the drama muted. But it is there, burbling underneath the seemingly drab story as Herz wanders the city, picks over his past, and tries, ineptly, to start or restart relationships. Now that he is free—finally—to do what he wants, he cannot decide what that is. He finds himself reduced to “hoping to catch life on the wing, and to make himself into a semblance of gentlemanly old age which others might find acceptable.”

As with all of Brookner’s novels (I’ve read 17 out of 26), there is much going on under the surface of this seeming simple novel. Multiple themes are there to be teased out. And her polished prose satisfies something in me that no other writer’s work does.

Do you ever wonder about the inner life of a seemingly ordinary person, perhaps someone you see in the supermarket or in the post office?