When I enter the world of a poem or story, I expect to be entering the author’s mind through the world they have created. Nowhere is this feeling stronger than in reading Graham’s poetry.

I know that each poem is carefully crafted, yet I feel a rare immediacy. I am in the presence of a mind in conversation with itself, breathlessly carried from one thought to another, whether the flow is tumultuous or a slow stream or even stuttering drops, a trickle that comes and goes.

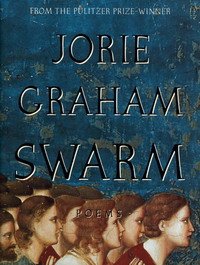

This collection, more than the others I’ve read or tried to read, is something to absorb all at once, a perhaps-coherent whole. Yet for all the time I have sat with it, I cannot give you a thumbnail description.

It describes not so much an epiphany—Graham has long stood out against poems that offer such a moment, such a resolution—as a grappling with a moment of profound change. In some poems she takes on a persona such as Agamemnon, Calypso, Eurydice; others read like journal entries, while still others are prayers or explorations of what it means to live a life or to lose it.

Graham’s poems can be difficult to read. A Modernist, she treats narrative and even language itself as suspect, constantly doubling back on herself, doubting herself, exposing herself. Crusty critic William Logan says, “Graham makes you wish stream of consciousness had never been invented.” Yet even he praises her “sprezzatura.”

It is her daring that thrills me, her going all out even if it means discarding forms and traditions and the poetic line itself.

I also appreciate how she attaches value to the moments of our lives, how she finds joy in small things. The poem “2/18/97” begins:

Of my life which I am supposed to give back.

Afterwards.

Having taken part in it.

She goes on to name some of the things to give back.

. . .the gentle lawns of this earth.

A sudden rain sweeping the petals along.

And pebbles the rain won’t move.

And these bodies . . .

The poem is more than these moments. It is an argument with the “soil that brightens and darkens,” that demands we live and later that we die. It is a holding close of our treasures even as they slip away:

children playing music on their knuckles,

feet skipping, dirt tossed round and then resettling on

their prints

where dance steps are

for just a moment longer

visible—

It is a vision of a god, a breath, a giving up, and that which will not be given up.

Yes, her poems can be difficult to read. But if you sit with them for a while, you may find the words—mistrusted as they are—opening. You may find new ways of being in the world.

Have you been reading any poetry lately? Share in the comments.