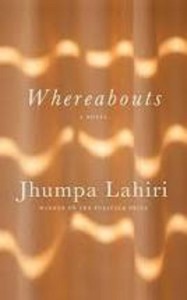

Subtitled A Novel, this book is a collection of short vignettes by an unnamed narrator, each named by where it takes place: “On the Sidewalk,” “In the Office,” etc. A picture gradually emerges of a 45-year-old woman in an unnamed Italian town whose “heart” is not really in her new teaching job, a woman who says, “Solitude: It’s become my trade.”

She seems very alone. Her colleagues keep to themselves. She has a few friends, one a married man with whom she might have once been involved with. This is just the kind of liminal relationship that interests me, but Lahiri doesn’t follow up with it, though the narrator runs into him and his wife a few times.

Some of the fragments have to do with the narrator’s parents. Her now-deceased father is remembered fondly despite his penny-pinching ways, but her relationship with her mother is strained. In one piece where Lahiri’s glorious use of language peeps out, the narrator says her mother always kept her close: “She protected me from solitude as if it were a nightmare.” Even now, her mother wants to recreate that bond, “blind to the small pleasures” of her daughter’s solitude.

Overall, though, the prose seems to me more pedestrian than I would have expected of this author whose other books have astounded me. The plot, too, is obscure: brief, seemingly unconnected incidents recounted by a person so reticent she can only share the barest details.

I suspect these limitations come from Lahiri having written the book in Italian, a recent language for her. Working myself on learning that language, I’m in awe at her accomplishment with this, her third language.

I’ve also tried writing in Italian and translating English into that language, and failed. I can use a dictionary as well as the next person, but I don’t know the connotations that have accrued to words, the cultural references evoked by certain phrases, the slang. It’s too easy to use a word innocently, not knowing what it conjures up for a native speaker.

My only recourse has been to write very simply, using basic vocabulary. I wonder if that isn’t what the author has chosen to do here. My own failures make me even more appreciative of the moments when her language sings, such as when she says of a father and daughter who run a trattoria that, coming originally from an island, they have “stored the sun in their bones.”

The lack of names—was the island Capri, Sardinia, Lampedusa?—adds to the disconnected feel of the book. The little vignettes are like leaves floating in a pond, sometimes touching briefly before slipping apart. The challenge is to make these seemingly random pieces hold the reader’s interest.

I love the concept of locating each piece so precisely—“At the Ticket Counter,” “On the Balcony”—while withholding any identifier that would anchor them in our world. Although I miss Lahiri’s beautiful language, I love the way the style she’s chosen for this novel reflects the narrator’s self-sufficiency. Other reviews mention the narrator’s loneliness, but I see her as positive about the solitude she has chosen. Yes, she has casual encounters and a few relaxed friendships, but prefers to walk the world alone. She betrays no angst and no regrets about her choice.

The fragmentary form of the book reflects what our lives are actually like. One of the greatest challenges of writing memoir is finding a narrative arc in our messy lives. In this novel, Lahiri has chosen to present a messy life without a narrative arc. It is an experiment in form and language that leaves me with the haunting portrait of a fictional woman I wish I knew more about.

Have you read any of Jhumpa Lahiri’s books?