There are many ways to write a memoir. You can make it a mostly chronological narrative of a particular time in your life—a small, self-contained period—as I did in my memoir Innocent. Still working chronologically, you can hopscotch through the years following a particular object or relationship, as J. R. Moehringer did in The Tender Bar. You can concentrate on a particular incident and explore how it ripples through the rest of your life, as Marguerite Duras did in The Lover.

You can abandon chronology and narrative altogether and piece together small bits of memoir, as Marion Winik did in The Book of the Dead or Denise Levertov in Tesserae. This may seem easier to the novice memoirist since you only need to write little bits at a time. The difficulty comes in stitching them together. Whether you want them to create a pattern or simply be a crazy quilt, the pieces have to work together. They have to be set against each other such that they make smooth reading. It’s actually far more difficult than a traditional narrative.

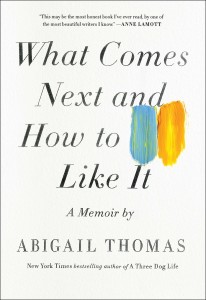

This is the task Thomas has set herself here. She says, “I hate chronological order. Not only do I have zero memory for what happened when in what year, but it’s so boring.” These pieces, which range in length from a sentence to a page or two, do cohere into a satisfying whole, in part because of her consistent voice, but even more because they circle around a single theme: Timor mortis conturbat me—fear of death disturbs me—comes from the Catholic Office of the Dead. She explores what can sustain us in the face of our inevitable end.

This body of mine, the one in pink pajamas, the one hanging on to her pillow for dear life, these pleasant accommodations in which I have made my home for seventy years, it’s going to die. It will die, and the rest of me, homeless, will disappear into thin air.

Thomas tells us about her simple, everyday life, stitching together her love of painting on glass, being with her children and grandchildren, napping with her dogs, meeting up with old friends, and so on. One of the main threads in the pattern is her longstanding—over 30 years—platonic friendship with Chuck. These are the things that sustain us.

Unfortunately, this piecemeal format doesn’t allow us stay with any issue or situation long enough to care deeply about the characters. Another obstacle is that these people are leading privileged lives, although Thomas is open about her challenges: three marriages, life as a single mother, her husband’s brain injury and subsequent death, her daughter’s breast cancer, her own struggle with alcohol and nicotine.

For a memoir to move a reader, the author must make themselves vulnerable, which she does. At times, though, I felt she was sharing too much about her flaws; some pieces made my sympathy for her fade.

Then comes beautifully written insight such as the piece “Out of the Blue” where her daughter tells her of a disturbing memory. Thomas ends with “This is the kind of memory I have always thought needs to be remembered by someone else after the original owner is gone.”

Then a few pieces later, she talks about her childhood visits to her grandmother’s house and how the scent of privet flowers—one of my particular favorites—filled those days; the path to the beach was lined with privet bushes. She says to Catherine, “The smell of privet is the smell of summer for me.” Catherine responds, “Yes, Mom. I know. Your memories are my memories now.”

I love this idea. Thomas asks Chuck what happens when we die. He responds, “You live on only insofar as others continue to think about you. Then you fade and blink out.” As friends, as parents, as writers, we seed our memories and stories for others to carry forward.

What memoir have you read that has stayed with you?