Thirteen-year-old Leni Allbright is used to her family picking up and moving on the spur of the moment. Now, her father Ernt, having lost yet another job, has decided to move them to Alaska where they will live off the grid on land he has suddenly inherited from his Vietnam War buddy. Leni hopes this will be the new start that will make everything okay and—a great reader—she’s excited to be going to the place Jack London called the Great Alone. Her frail, former hippie mother Cora will follow her husband anywhere.

Mama had quit high school and “lived on love.” That was how she always put it, the fairy tale. Now Leni was old enough to know that like all fairy tales, theirs was filled with thickets and dark places and broken dreams, and runaway girls.

Leni knows that her parents have a deep and abiding love for each other, a bond that held up during Ernt’s long absence in Vietnam and through his often violent behavior since his return. The small family has no homesteading skills, other than Ernt’s mechanical aptitude, and as assets only the rundown VW bus Ernt has bought with almost the last of the money.

When they finally arrive at their land, they find a tiny cabin with no electricity or running water, set in a yard full of old animal bones, rusty machinery, and other junk. Ernt’s friend never had a chance to start fixing the place up before leaving for Vietnam where he died.

It’s 1974. Kaneq is barely even a town. Its people, mostly living in far-flung homesteads, are fiercely independent even as they pull together to help each other when needed. And help is often needed in this unforgiving environment. Luckily for the Allbrights, their neighbors, especially the family of Ernt’s buddy, show up to sort out the cabin and get the family started on a garden, chicken coop, woodpile, and other necessities. Winter will be coming all too soon.

And with it, Ernt begins to fall apart, undone by the darkness—eighteen-hour nights—and cold. He becomes increasingly paranoid and jealous of a wealthy neighbor who is attracted to Cora. He drinks too much and prepares for the coming collapse of society by accumulating guns. His abuse accelerates, but Cora and Leni always forgive him and keep his violence a secret. At the small schoolhouse, Leni meets the son of the neighbor—the only other child her age—and they become best friends.

While much of the prose is rich with detail, especially of the landscape, I found the story lacked subtlety. The characters are all stereotypes: the violent and alcoholic Vietnam vet with PTSD, the brainless hippie who thinks love will cure all, the emotionally and physically strong (despite her obesity) Black woman who runs the general store and cares for Leni in ways her parents don’t, a Romeo and Juliet couple. Every character is either all good or all evil.

And the stereotypes are dangerously naïve: you should give up everything for true love; Black mammies exist to save/serve White people; abused women love their partners too much to leave them; all vets are dangerous maniacs. The author even perpetuates the urban myth that people called vets baby-killers when they got back from Vietnam. It’s possible that happened once or twice, but the people I knew protesting the war would never have done that. We cared about the soldiers; we wanted to bring them home, out of danger. The right-wing media played the baby-killer tape for their own purposes the same way they did Benghazi and the Welfare Queen.

This could have been a fascinating story about the tension between being independent—the U.S.’s cowboy myth—and being part of a community. It could have been a thoroughly interesting story about the process of learning about the land, making mistakes, finding ways to survive. Instead we get a story about abuse and crazy preppers. The story entirely skips over the part about adapting to Alaska, jumping from the initial cluelessness to a comfortable existence with all systems humming.

Thus the family’s success seemed unrealistic to me, not just their ability to survive the winters, but also their finances. They have no money, yet Ernt always has cash for whiskey.

Aside from the characters and stereotypes, I found the plot lacking nuance. The first half is fairly slow, which didn’t bother me, but the second half turned into a whirlwind. Writers are told to constantly make it harder for the protagonist, but this story goes too far: disaster piled upon preventable disaster, bad luck and bad choices, misery and pain.

I found there wasn’t much to hold me. The story became more and more sentimental, which actually made it harder to engage emotionally. I didn’t sense the love for Alaska; characters talked about loving Alaska, but that’s not the same thing. The cartoonish characters left me cold; I didn’t ever sense the love between the young couple, much less between Ernt and Cora—their famous love that was supposed to excuse everything, including the damage to their daughter.

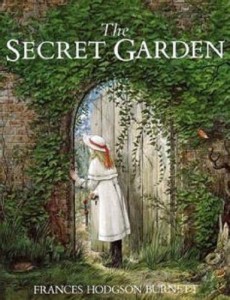

The one emotion I did feel was the pain: Cora’s and even more Leni’s. I know there are complicated reasons for staying in abusive relationships, but True Love as an excuse makes me roll my eyes. Self-centered parents who ignore how they are damaging their child make me want to spit. Leni, like Jane Eyre and countless other unloved children finds her refuge in books.

Books are the mile markers of my life. Some people have family photos or home movies to record their past. I’ve got books. Characters. For as long as I can remember, books have been my safe place.

I wanted to like this book. Stories about people confronting a new and challenging environment interest me, and Alaska as a setting is a plus. I did find the writing engaging enough to keep reading it, though I set it down often. Ultimately, though, I was disappointed. Of course, your mileage may vary, and many reviews praise this novel.

What stories about Alaska have you read?