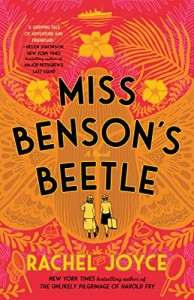

London in 1950 is still recovering from World War II, with food rationed, ruined buildings being cleared, another generation of men wiped out, and women chucked out of their wartime jobs. Middle-aged spinster Margery Benson finally cracks and quits her job teaching domestic science in an elementary school with out-of-control children. She decides to set out on the adventure of a lifetime: an expedition to New Caledonia to find a mythical golden beetle.

She became fascinated with the golden beetle in 1914 when she was 10, and her father showed her a book of unknown creatures, meaning those referenced in ancient books but not yet found in real life. Later she met an entomologist at the Natural History Museum who taught her about beetles and collecting, making her long for the kind of journey she now has the training for.

Advertising for a French-speaking assistant, Margery gets only four responses, one an ex-POW still suffering from physical and psychological wounds, and two women who drop out, leaving her with the most unlikely assistant of all. Enid Pretty is a bleached blond woman in a pink suit and pompom sandals who never stops talking. Her French is limited to a mangled bonjour; her knowledge of entomology is nil, and she has no passport.

With much finagling and last-minute surprises, the odd couple manages to make it onto the ship to New Patagonia. Margery is not sure she can bear even one day in Enid’s company, much less weeks on the boat and months in the field. What she doesn’t know is that they are being followed by Enid’s shady past and the ex-POW who believes he should be leading the mission.

This book was the vacation I didn’t know I needed. Sure, there were moments that strained my credulity, but I was happy to go along for the ride.

Much as I enjoyed the scene setting, whether in a crowded ship stateroom, a British consulate tea party, or a remote jungle village, what fascinated me most was how the author managed to bring together the most incongruous elements. We have a dangerous adventure that’s also a madcap comedy. We have a woman with no credentials trying to mount an independent scientific mission, while beset with lost luggage, visas held up by recalcitrant bureaucrats, and tropical illnesses. Most of all, we have an unlikely friendship that grows organically throughout the book.

I also appreciated the way the author respects the voice of even the minor characters, such as the wife of the consul and the mousy woman who stands up to her, the French police and the native storeowner, not to mention the ex-POW himself. These could easily have been sketched in as stock characters, but Joyce presents them with care and insight.

If you’re looking for a break, join Margery and Enid on the adventure of a lifetime. You’ll find thrills and chills and a lot of laughs.

What books do you read when you want a virtual vacation?