In this chapbook of poems, a young woman, Hélène, works in a factory-convent in 19c France weaving silk. As described in the epigraph from Foucault girls entered these factory-convents at thirteen and stayed for years, confined and watched over by nuns. Their wages were kept back and only given to them when they left at 21, after food and lodging were deducted.

Hélène’s factory is located in the village of Jujurieux in Ain, not that she knows the village; enclosed by the factory walls, her days consist of “nine hours weaving and three hours teaching” by which she means being taught. She speaks admiringly of “the benefactor” who has created this golden prison, who “offered something other than work on farms.”

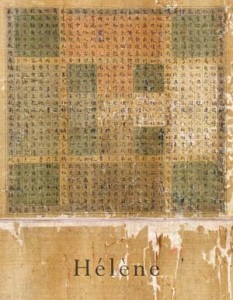

The first poem is so dense with images, images without context, that the reader is overwhelmed. Only gradually do they begin to cohere and convey meaning. Thus we experience what Hélène, must have felt on first entering the enclosed world of the factory and her awe at seeing the glorious silk tapestries that she will have a hand in creating. The book’s beautiful cover gives us a taste of that glory.

Other poems are bare statements, stripped to the bone yet still carrying the weight of the story that emerges from these pages. It is Hélène’s story, of finding a friend among the “mummied” girls, of her own fall and its consequences. Poe gives us only the ghost outlines of a story, leave more than the usual space for the reader to fill in with her imagination.

Hélène’s story is much more than this simple outline. As her loneliness and restlessness grow, she escapes into a fantasy of living in China herself, feeding mulberry leaves to the worm, imagining how the secrets of silk “wandered via nomads along elongated slender grasslands.”

The other epigraph is from Chuang-Tzu about the use and limitation of words. Together these epigraphs signal the twin concerns of this book: imprisonment and art.

The brevity of the poems reinforces the sense of confinement, the silencing of the girls. Hélène compares herself to the work in cocoon, saying “Feel but tell no one a way of being.” Even the accents of her name seem to enclose her.

Poe uses additional quotes from Chuang-Tzu to signal and suggest hinge moments in Hélène’s story. Poe also makes effective use of the Japanese poetic technique of the kakekotoba, or pivot word, one that carries two meanings, such as when she says of the factory’s architecture “it looms straight down.” Hélène becomes entranced with individual words and the world of meaning each can hold.

Gently, always leaving space for us to make Hélène’s story our own, Poe juxtaposes the beauty of the silk tapestries with the working conditions of the time. We cannot help asking ourselves what confines us and how we escape. As readers and writers, words are our tools and our drugs; they are the keys that open our memory and senses and imagination. Hélène’s story gives us room to ponder what we dream and how we are transformed.

What confines you? How do you escape?