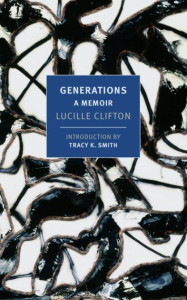

Lucille Clifton is one of my favorite poets and a huge influence on my writing. I was privileged to hear her read more than once. In this memoir, originally published in 1976 and now a new edition from New York Review Books, she brings a poet’s sensibility to crafting her story.

The chapters, while prose, in their brevity exhibit the conciseness of poetry; anything not absolutely necessary is pared away, leaving the kernel. And you, the reader, bring your own understanding and experience to fill in the spaces. Each anecdote, each sentence becomes something precious because you know it is there for a reason.

She begins with an anecdote of a White woman who, after seeing a notice in the paper, thinks they might be related and offers to send Clifton a history of the family that she has compiled. Yet she does not recognise the name of Clifton’s father. “Who remembers the names of slaves?” Clifton asks. “Only the children of slaves.”

Unlike autobiography which covers your entire life and is as objective as possible, memoir includes only a small piece of your experience, usually a limited time frame, sometimes restricted to a particular theme or relationship. It is more subjective, understood to be the author’s perceptions.

Clifton, writing just after her father’s death, intersperses fragments of the family gathering for the funeral with the stories he has told her about the family members who shaped him, especially Caroline Donald, who was “ ‘born free among the Dahomey people in 1822 and died free in Bedford Virginia in 1910.’”

“Mammy Ca’line raised me,” Daddy would say. “After my Grandma Lucy died, she took care of Genie and then took care of me. She was my great-grandmother, Lucy’s Mama, you know, but everybody called her Mammy like they did in them days. Oh she was tall and skinny and walked straight as a soldier, Lue. Straight like somebody marching wherever she went.”

You can hear the poet’s ear for the music of words, the way she captures the rhythm of a person’s voice, suggesting dialect without tortured punctuation.

Through traces as delicate as sumi-e, Clifton gives us other family members: Genie, her father’s father with his withered arm and success with the ladies; wild and headstrong Lucy who was hanged for killing a White man; Clifton’s mother Thelma, brother Sammy and half-sisters Jo and Punkin.

The details are what break your heart, such as a teenaged Caroline married off at to another slave, 45 years older than her. “ ‘Oh slavery, slavery,’ my Daddy would say. ‘It ain’t something in a book, Lue. Even the good parts were awful.’” There is much that is of the time: Clifton’s father came north to work in a steel mill during a strike, part of the Great Migration, and bought not only a house but also a dining room set, the first Black man in Depew to do so.

Clifton draws strength from her ancestors. It is Caroline’s clarion call that echoes through the generations: “ ‘Get what you want, you from Dahomey women.’” Clifton’s bold choices shape her adult life; she is the one to comfort her sisters and assure them that their daddy will not haunt them.

The quotes from Walt Whitman for each section help make this memoir a celebration of the lives intertwined through the centuries and going on. With this powerful memoir, we will remember their names: Caroline, Lucy, Samuel, Genie, Thelma, Lucille.

Have you read a memoir that seemed like poetry?