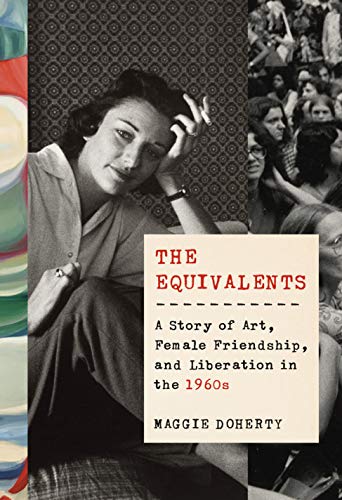

Subtitled A Story of Art, Female Friendship, and Liberation in the 1960s, Doherty’s fascinating new book tells of a “messy experiment” at Radcliffe College. President Mary Ingraham Bunting became concerned with what happened to the graduates of this all-women college. Since at that time women were expected to marry and spend their time caring for their husbands and family, these educated women were expected to give up their academic or creative pursuits, or reduce them to hobbies, in order to become what Virginia Woolf called “the angel in the house.”

Remembering her own career as a microbiologist–and now college president–while raising a family, Bunting created the Radcliffe Institute for Independent Study in 1960. Fellowships provided a stipend, office space, and a like-minded community to help women advance their careers as scholars and artists while also caring for a family. For a two-year period, the Institute would provide a fellow the prerequisites for creative work, as described by Woolf in her famous essay “A Room of One’s Own.”

Doherty concentrates on a few of the first fellows: poets Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin, writer Tillie Olsen, sculptor Marianna Pineda and painter Barbara Swan. They called themselves The Equivalents per the Institute’s requirement “that applicants have either a doctorate or ‘the equivalent’ in creative achievement.” Her extensive research underlies this engaging story of five very different women and their creative journeys. And the book is so much more: a cultural history of the time, an in-depth look at creativity—what enhances it and what destroys it—and an examination of privilege.

I confess that it is the latter that most interests me because, after all, even in the 1950s and 1960s, while White women in droves were immersing themselves in being housewives, Black and working class women were already working while trying to raise a family. I appreciate that in covering the nascent second wave of feminism, Doherty includes the Black women’s movement. While acknowledging it isn’t “her” experience, she does examine the very real problems Black women had with what became the mostly middle- and upper-class White women’s movement.

Tillie Olsen’s story provides a needed corrective to Sexton’s upper-class privilege and that of the others’ somewhat lesser privilege. Olsen was “a first-generation, working-class American, an itinerant, and an agitator” who said outright that “the true struggle was the class struggle.” After early publication and literary acclaim, she had been side-tracked by the overwhelming labor of house, family, and dead-end job. Eventually the author of the best-seller Silences, she was alert to all the things that keep us from creating.

The way Doherty sensitively examines these women’s different struggles and achievements lifts this narrative above the ghoulish interest in Sexton’s suicide attempts and the tendency to concentrate on those artists who have been anointed as important—almost exclusively White males at the time, or the handful of women championed by them—to look at a broad range of circumstances and personalities.

She acknowledges the privilege but goes deeper. As Olsen said, “There’s nothing wrong with privilege except that not everybody has it.” This is as true today as it was in the 1960s. Fellowships, grants, prizes are wonderful but not everyone has the resources—time and money—to pursue and take advantage of them. As a single parent working two and sometimes three jobs to support my family, my own writing career had to be mostly put on hold for years.

I highly recommend this book to anyone who is interested in the creative life and what can inspire or hinder it. It’s also a wonderful portrait of that era and of these remarkable women.

Do you have a room of your own?